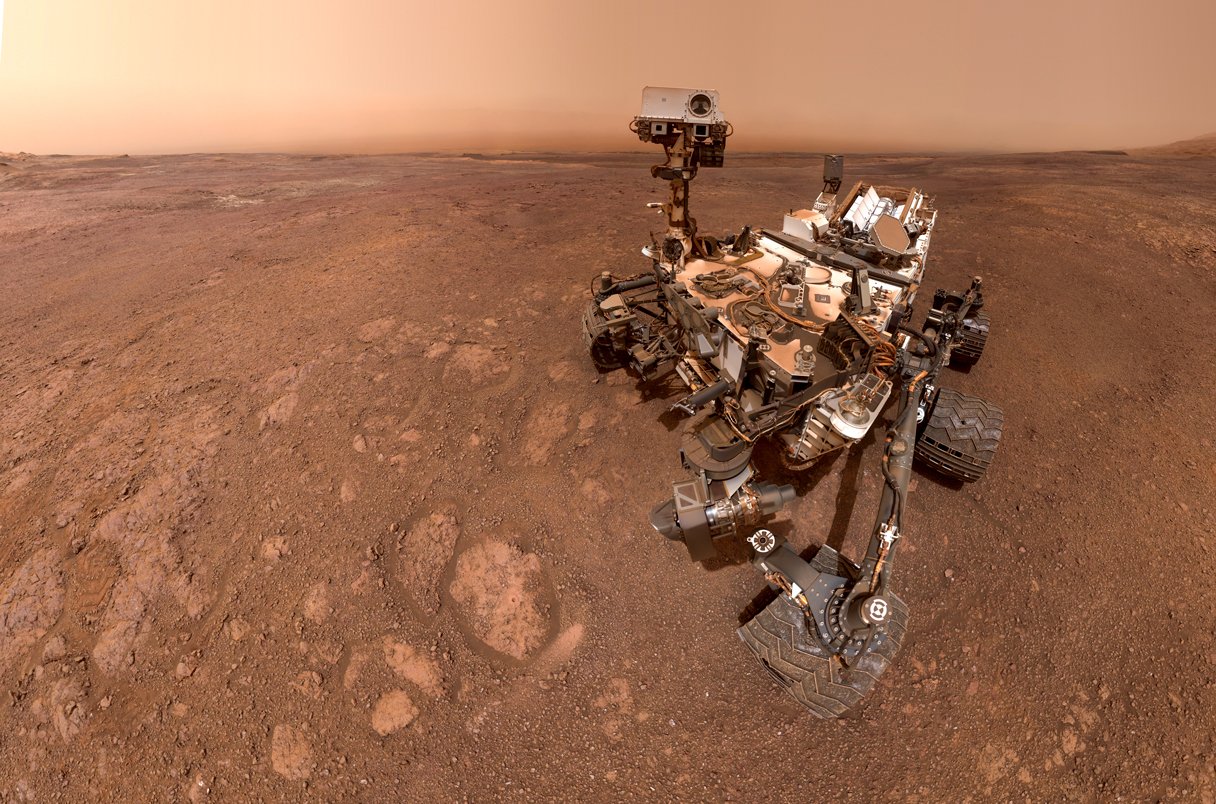

PICTURED: Curiosity rover taking a selfie. PC: NASA/JPL-CALTECH/MSSS

Story at a glance…

-

Curiosity rover has discovered samples of sedimentary rock enriched with the organic form of carbon.

-

Scientists present three explanations, all of which fit the existing data, but require more.

-

As well as laying out the potential for ancient microbial life, the findings also describe future discoveries which would bolster or scupper the possibility.

Despite the shiny new Perseverance Rover’s role as an astrobiologist, its predecessor, Curiosity, has found the first major discovery to suggest ancient microbial life existed on Mars.

What did it find? Large amounts of very light carbon isotopes in rocks at the bottom of an ancient lake—the kind one observes in methane gas produced by organic life, for example during photosynthesis, and not the kind seen from non-organic methane like what comes out of an undersea thermal vent.

That’s the major sticking point behind Christopher House et al.’s new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, which details three possible explanations for the finding; two nonorganic, and one organic.

“Three possible explanations are the photolysis of biological methane released from the subsurface, photoreduction of atmospheric CO2, and deposition of cosmic dust during passage through a galactic molecular cloud. All three of these scenarios are unconventional, unlike processes common on Earth,” the authors write.

Like professional scientists the team did their best to disprove the elephant in the room, but the fact that one of their three explanations involves a once in a 100-million year phenomenon, means there’s a genuine interest in pursuing the possibility that we found evidence of ancient microbes on Mars.

Life finds a way (lazily)

The samples gathered came from the laser spectrometer instrument suite on the belly of the Curiosity rover, which melts samples of rock under a powerful laser to measure the contents of the gas released after. The work is a real toil, and Curiosity has collected and analyzed little more than 30 drilled samples on Mars between August 2012 and July 2021.

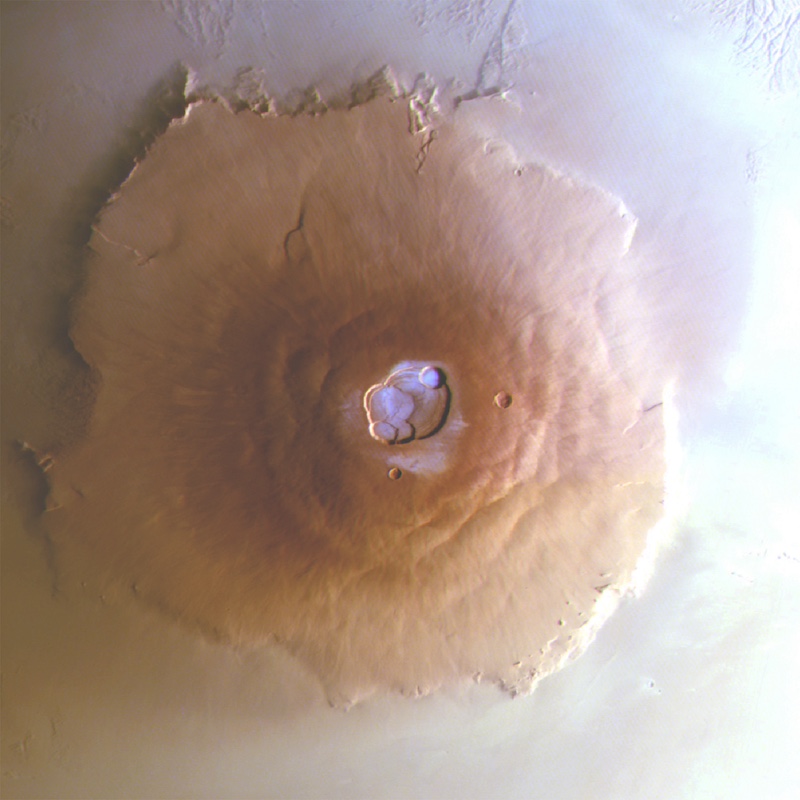

Rock samples taken at the bottom of Gale Crater released methane under the heat from the laser, inside of which were carbon molecules with 12 neutrons. This is a lighter, more stable form of carbon that life seems to prefer, as it’s easier to divide than non-organic carbon-13 which is weighed down by an extra neutron. The ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-13 was 70 parts per thousand higher than Earth-based references.

The ratio was most in favor of carbon-12 along the heights of Gale Crater, and in topographically high areas within the crater’s bottom, suggesting the carbon-12 was deposited when it came down from the atmosphere billions of years ago.

“We’re finding things on Mars that are tantalizingly interesting, but we would really need more evidence to say we’ve identified life,” said Paul Mahaffy, who served as the principal investigator for the chemistry lab aboard Curiosity until retiring from NASA’s Curiosity control room in December 2021. “So we’re looking at what else could have caused the carbon signature we’re seeing, if not life”.

“On Earth, processes that would produce the carbon signal we’re detecting on Mars are biological,” lead-author House told NASA. “We have to understand whether the same explanation works for Mars, or if there are other explanations, because Mars is very different”.

Their current bio-explanation is that there once were subsurface microbes feeding on slightly light carbon-12 released from Martian magma. Their byproduct of methane was then eaten by surface microbes, creating even more carbon-12, before releasing it into the atmosphere where it eventually came back down through the Martian carbon cycle and settled into the sedimentary record. This explanation was reinforced by the reduced sulfur content in the samples that showed higher levels of carbon-12, because marine methane oxidization by microbes is coupled with sulfate reduction.

“Overall, there is, however, no supporting sedimentological evidence for microbial methanotrophy on the paleosurface discussed here,” the authors conclude.

PICTURED: This mosaic was made from images taken by the Mast Camera aboard NASA’s Curiosity rover. It shows the landscape of Gale crater and the general location of where Curiosity drilled the Edinburgh sample which was enriched in carbon 12. PC: NASA/Caltech-JPL/MSSS.

Appropriately conservative

Two other explanations that fit the observational and geological evidence were furnished by House et al., the first is that carbon dioxide in the early Martian atmosphere was under pressure by high levels of UV light, which caused new carbon-containing molecules to form and settle to the surface.

This happened through photolysis, or photodissociation, which has been shown in studies to create organic aerosols by breaking down methane in the Martian atmosphere, even today. If this were happening, the authors write, when the proposed subsurface environment was exposed, it could account for both the reduced sulfate and increased carbon-12.

The third explanation is that Mars passed through a cloud of cold carbon-12-rich stellar dust, which can be predicted to happen every 100 million years.

Astronomers have studied meteorites that have passed through such clouds, and found that the ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-13 can be extremely high. However as well as being an enormous coincidence, these gas clouds are known to create system-wide cooling events, and no evidence of ice has been found in the sedimentary layers Curiosity is reaching.

All this hypothesizing has been lauded by colleagues, such as Mark Harrison, a planetary scientists who spoke with Science Magazine about the paper, saying “the authors are appropriately conservative”. However there’s an old saying about where there’s smoke there’s fire, and these new findings, come two years after Curiosity detected plumes of methane gas exiting the surface.

Curiosity lacks the equipment to measure the carbon-12 content in such plumes, but if it were as high as the recent sampling, then things could get really interesting.