PICTURED: Researcher Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, and his colleague Concepcion Rodriguez Esteban.

Medical science is now becoming very comfortable with the evidence that caloric restriction, meaning a period or a diet of chronically-reduced calories but not micronutrient amounts, is one of the most effective delayers of aging.

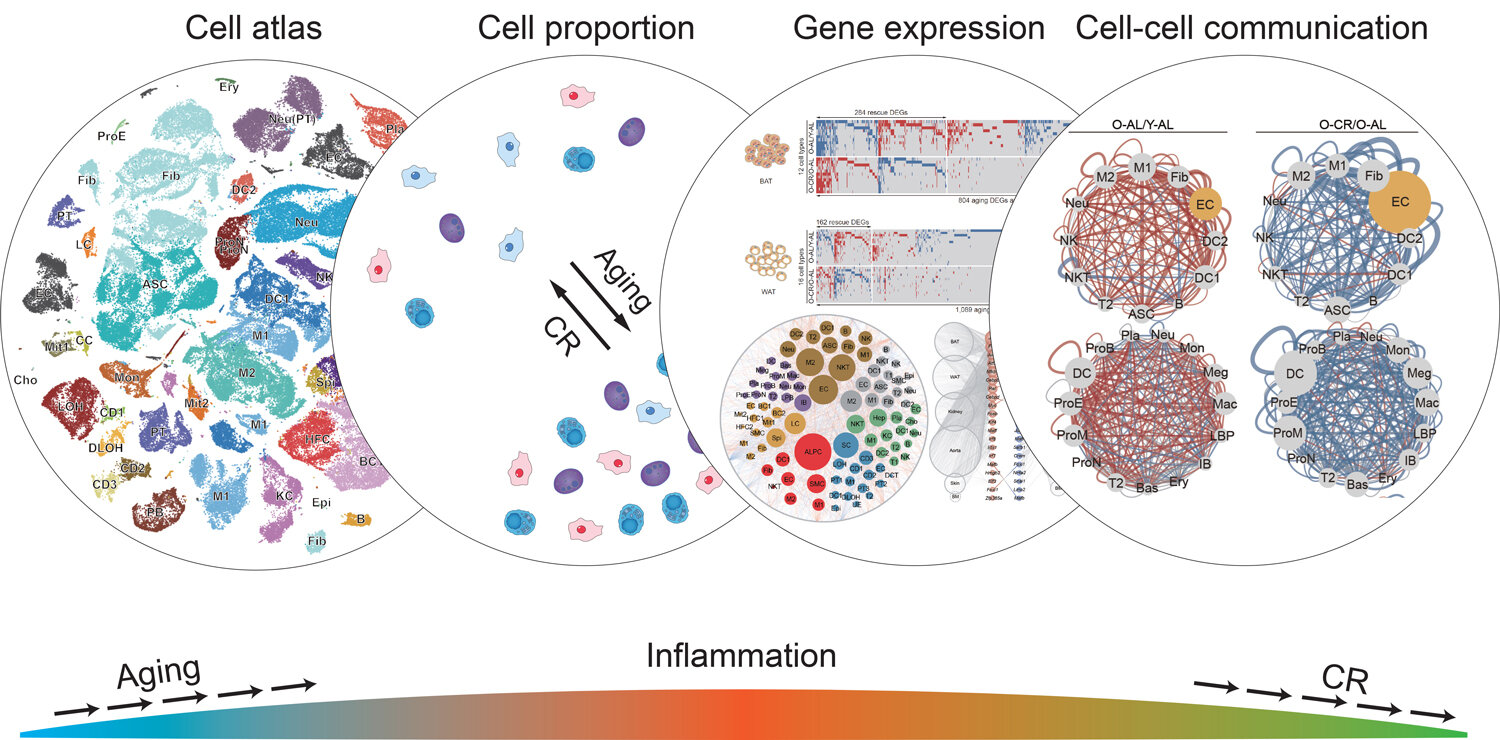

A new study published in the journal Cell features the most comprehensive single-cell map of the genetic reactions to aging under calorie-restricted conditions in rats that’s ever been done. For researchers working on caloric-restriction as an alleviation of age-related cognitive, muscular, or metabolic degeneration, the paper is a gold mine of data.

The rats in the study were placed on a calorie-restricted diet from 18 months of age and 27 months of age – about the same quadrant of life as if a human went on a diet at 50 and stopped at 74. At the start of the trial and again at the end, 168,703 cells from 40 cell types in the 56 rats were measured for activity using single-cell genetic sequencing technology. The cells came from organs like the liver, kidney, aorta, skin, and brain, and other tissues like the bone marrow and muscle.

The results, as detailed on a report from the Salk Institute for Biological Studies website, seems to be something like “eat less, live longer”.

“We already knew that calorie restriction increases life span, but now we’ve shown all the changes that occur at a single-cell level to cause that,” says Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a Salk Institute researcher who assisted the production and authoring of the new paper.

“This gives us targets that we may eventually be able to act on with drugs to treat aging in humans,” said Belmonte.

Eat less, live longer

While it may seem entirely counterintuitive to the layperson, the process of metabolising food cannot be reconciled in the body with other processes, such as autophagy, the cellular cleanup and repair process. Chronic calorie restriction leads to a mimicking of many of the benefits observed in fasting. This is most prominently researched by Dr. Valter Longo, and the scientist maintains a fasting-mimicking diet program on his website.

In the rat trial, the genetic sequencing found that many of the standard genetic and cellular changes associated with aging were absent in rats on the calorie-restricted diet. In fact, even in old age, many of the tissues and cells of the aged rats on this diet more closely resembled those of young rats.

How close? 57 percent of all changes in cell composition and genetic transcription associated with aging that were observed in the tissues of rats on a normal diet were not present in the rats that were skipping lunch. A lazy scientist might say that a little more than half of age-related dysfunction was halted.

“This approach not only told us the effect of calorie restriction on these cell types, but also provided the most complete and detailed study of what happens at a single-cell level during aging,” says co-corresponding author Guang-Hui Liu, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Inflammation is everything

One of the most striking patterns which emerged from the gene sequencing was that the amount of immune cells produced in every observed tissue radically increased in response to aging, but that the diet attenuated this inflammatory expression – so much so that the Salk write-up described the calorie-restricted rats as being “not affected” by age-related increases in immune cell production.

“The primary discovery in the current study is that the increase in the inflammatory response during aging could be systematically repressed by caloric restriction,” says co-corresponding author Jing Qu, also at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

This is a major confirmation of earlier suspicions. In 2015, a breakthrough study by Japanese researchers found that in a cohort of 1554 Japanese individuals including populations of centenarians (100 years of age to 104), semi-supercentenarians (105+), as well as their offspring and some of their other relatives, levels of inflammation and not the length of telomeres (another potential marker for successful aging) predicted not only survival, but cognition and general capability.

The team of researchers from Salk and the Chinese Academy of Sciences is now trying to utilize this body of work in order to further the potential of anti-aging drugs by formulating the correct targeting and implementation strategies towards the increase of life and health span.

This could mark a serious change in human society. While fasting and calorie restriction are available to all of us as tools of health and wellness, there aren’t many who will commit to giving up their favorite meals – or certain mealtimes altogether for a benefit that may take 30-40 years to manifest.

However if we could take a pill that tricks our body into entering a calorically-restricted state even when it isn’t, people across the world could, provided results from human trials would be the same as in the rat data, routinely live to 100 or more years of age with cognitive and physical independence and very little adjustment to the way they prefer to live.