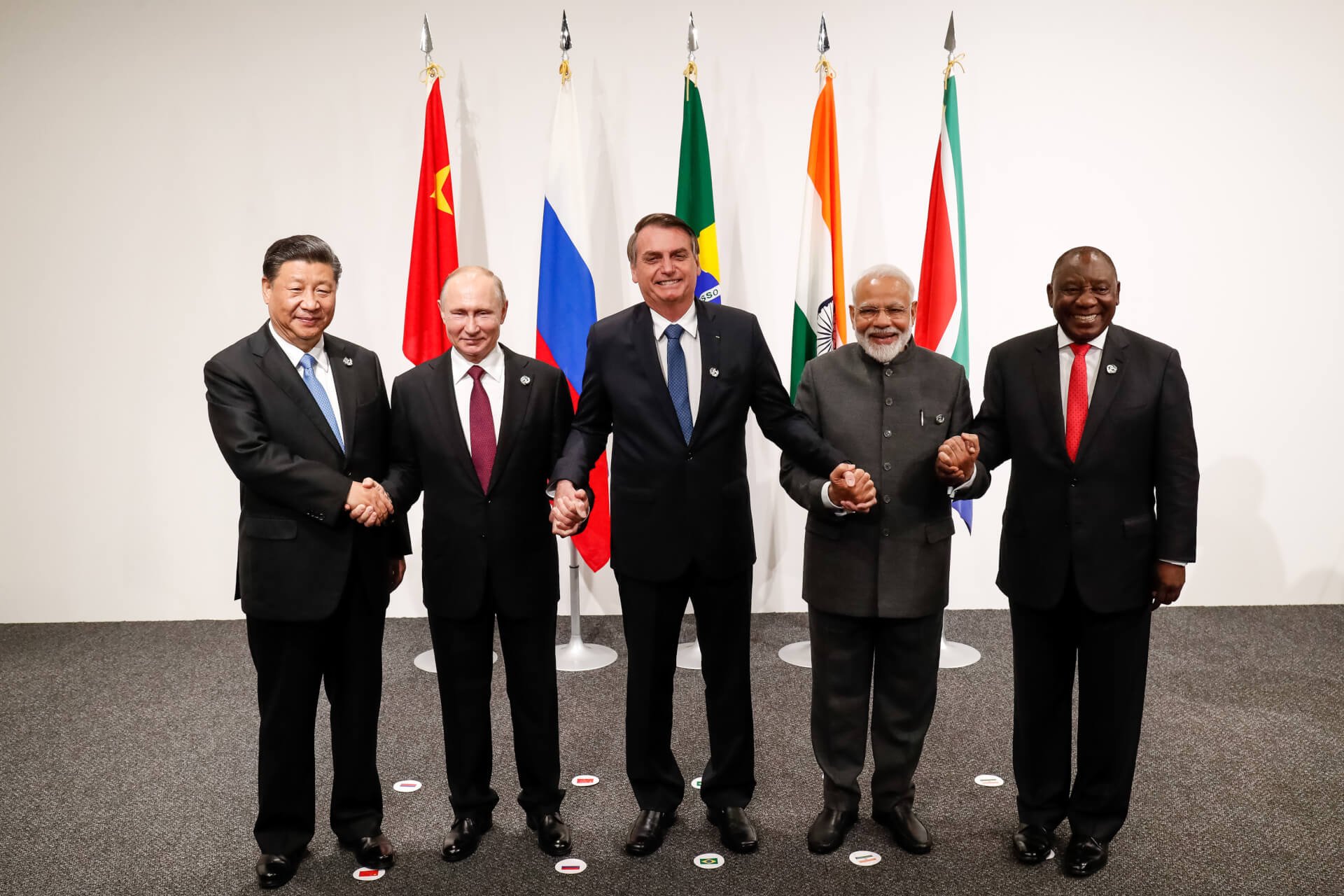

PICTURED: Chinese President Xi Jinping, President Vladimir Putin, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa.

The U.S. dollar remains the world reserve currency—declared by no one, but adopted by everyone. For decades, any bank has been able to use dollars to settle international debts and payments, but a new wave of fast payment options for the various economic blocs in the world could be challenging that status.

For starters, Russia, China and the rest of the BRICS countries—Brazil, India and South Africa, “are officially working on their own ‘new global reserve currency,’” as Statecraft recently reported.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has said the five nations were “developing reliable alternative mechanisms for international settlements” and “exploring the possibility of creating an international reserve currency based on the basket of BRICS currencies”.

It could be called the “Big R” or the “R Five” after rupee, ruble, rand, real, and renminbi. Together, the BRICS nations’ GDP is equal to slightly more than the U.S. in U.S. dollars. In 2021, it comprised 41% of the world population, having 24% of the world GDP and a 16% share in world trade.

Further out, the five most prosperous Southeast Asian economies, The Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia are preparing their own QR code-based fast payments system to rapidly conduct their internal trade of over $1 trillion per annum, no U.S. dollars necessary.

For example payments transacted in Thailand using an Indonesian app would be directly exchanged between rupiah and baht. The system could be ready as soon as November, reports Tech Wire.

While it’s natural that more digitally-distributed banking, finance, and payment systems will reach more parts of the world, it’s a law of monetary phenomenon that people tend to gravitate towards using the same monetary unit and institutions out of convenience, suggesting something in the dollar has become inconvenient.

Some inconvenient truths

Prolific journalist and author Eve Ottenberg suggests it’s a case that Western financial institutions have lost the faith of global economic actors who now consider it too dangerous to bank in countries who, for a long time, have had stable, useable currencies.

After the 2018 elections in Venezuela, Ottenberg points out, the UK government didn’t agree with the results, and simply lifted US$2 billion of the country’s national gold reserves that were held in Britain. Similarly, after the Taliban took control in Afghanistan, the United States froze access to US$7 billion held in trust for the previous government. Now that country is going through a famine that could kill millions.

During the now infamous “Freedom Convoy” protest in Canada, the world watched as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau simply closed off the bank accounts of over 200 private citizens worth CAD$7.6 million, shattering a long-standing financial reputation.

Now in response to the war in Ukraine, the West has seized US$700 billion in Russian private and public assets all over the world.

How much these acts of government financial strong-arming is dissuading countries like Indonesia or Brazil, or Argentina who recently it was reported sought BRICS membership, from trading in western currencies or banking in western institutions is difficult to say, but it’s out there now for everyone to see.

Furthermore, the lack of strength in a national currency is on full display all around the Southeast Asian bloc, and some BRICS members, as Pakistan, Laos, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, are all at various points of the same disastrous spiral of inflation and low foreign currency reserves.

There are two ways to strengthen a national currency: increase the scope of its use, or grow the domestic production of goods and services such that other countries need the national currency to import the desirable goods.

Increasing the ease and scope in the use of something like baht, or ruble, is a way to protect these countries during times when global supply of lower stage goods like oil, or higher order goods like microchips, are in short supply and prices are steep.

Additionally, the inflation of western reserve or strong currencies is becoming a real issue, especially for countries like China and others who together own nearly $9 trillion of U.S. sovereign debt at a time when the value of that debt may be falling drastically. Between 2020 and 2021 the value of total liquid money, savings, and money markets in the U.S. rose 33%. Nothing of the kind has ever happened at this scale before.

All that extra liquid will push the prices of goods up, severely limiting the purchasing power of the dollar. To wit, Global Data reports that price inflation around the world rose to 7.5% in July. up from 4.8% in January.

Countries that are wishing to enter the ranks of the first-rate and second-rate economic powers are looking at the currency landscape and deciding it’s time to strike out on their own for good, and the U.S. dollar may no longer need to prop up global trade and finance any longer.

If you think the stories you’ve just read were worth a few dollars, consider donating here to our modest $500-a-year administration costs.