Neurology has shown us that the body has but one onboard mechanism for preventing dementia in our later years: sleep. A new study now links shorter sleep duration during groups in their 50s, 60s, and 70s with increased risk of dementia.

The study used self-reported sleep data from a cohort of around 8,000 people, with the average age when the trial began in 1985 being 50.

The study shows higher risks of dementia in those sleeping six or fewer hours per night at the age of 50 or 60. There was also a 30% increased dementia risk in those with consistently short sleeping patterns from their 50s to 70s.

Contrastingly, the lowest incidences of dementia were observed in everyone, regardless of sociodemographic and cardiometabolic factors, that slept 7 hours or more a night at any point during the study period.

There were drawbacks of the study in that the data was self-reported, with only around 3,900 people having between 1 and 2 years of data collected by sleep monitors, which are not truly precise anyway.

Even still, the fact that the same effect was found when controlling for socio-economic, demographic, and health markers like mental health condition and cardiometabolic strength, is a good sign.

It’s a powerful discovery, and lends itself to a growing body of neurological evidence, evidence that also contributes to a possible mechanism that links the two phenomenon, the dementia and sleep duration, together.

Amyloid-beta: remember the name

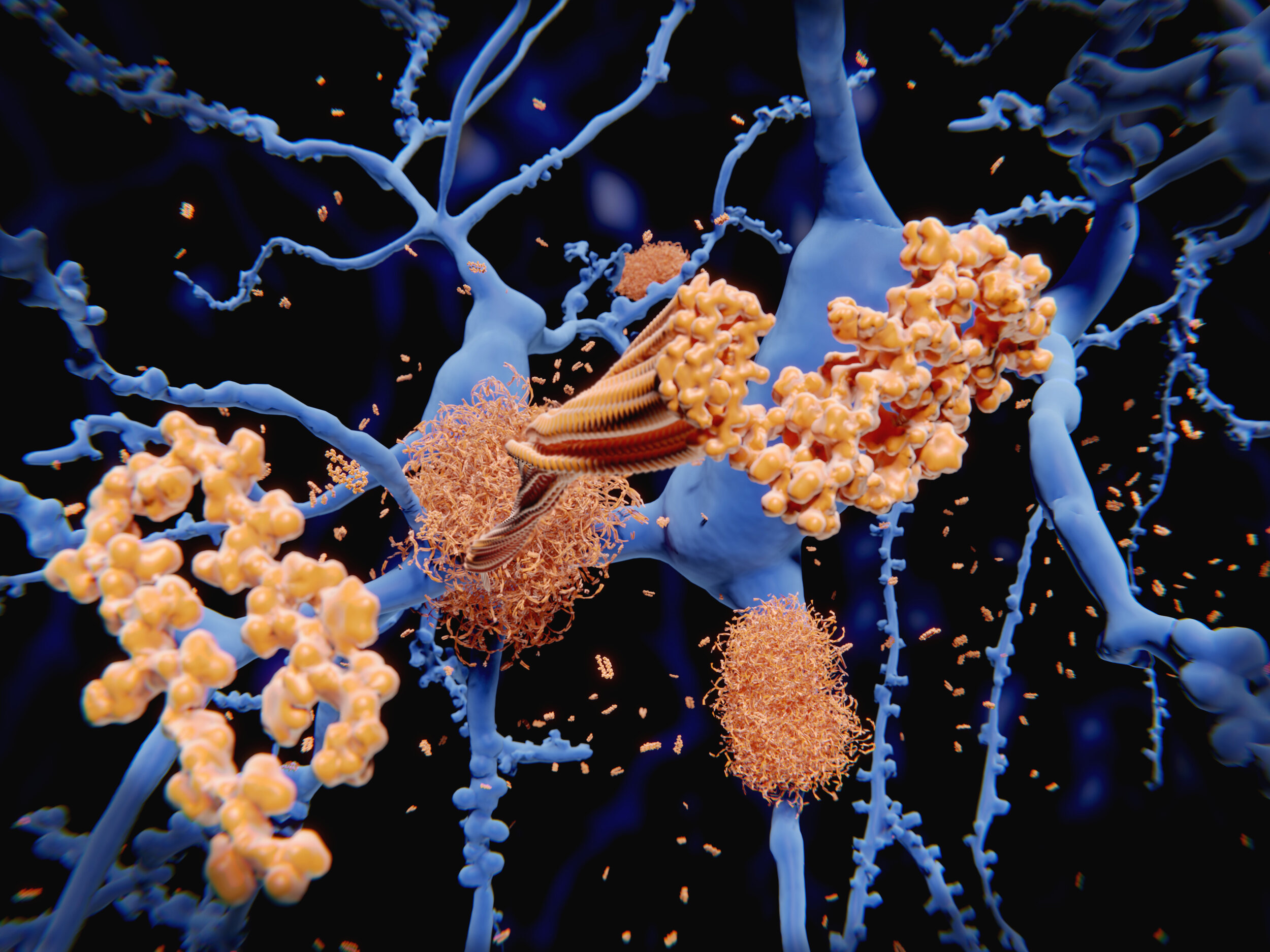

People who sleep less are found to be carrying greater amounts of a tau protein called amyloid-beta, which is sometimes referred to as a “plaque,” on the outside of their brain cells. This plaque is cleared away every night by cerebral spinal fluid produced by the glymphatic system.

The plaque builds up, coincidently (or perhaps not) in the regions of the brain associated strongest with memory, such as the neural cortex and the hippocampus, and regions that attenuate sleep, and it’s for this reason that amyloid-beta is the target of a number of failed and currently trialing dementia pharmaceuticals like aducanumab, solanezumab, gantenerumab, crenezuma, and belenbecestat.

If the plaque appears in sleep deprived people, and both are associated with dementia, how can we adjust our sleeping patterns to address this? As WaL reported in 2019, the secret is in the deep sleep.

Deep sleep, technically called slow or “delta” wave sleep, is just one period that makes up a total sleep cycle, and accounts for about 20% of total sleep time. It’s the hardest stage of sleep to achieve, but one which is the most restorative, says sleep expert Dr. Matthew Walker.

It’s also a stage that people spend less and less time in as they get older, meaning that preventing dementia, as the new study says, in our 70s might not be possible at that point.

This was discovered in a study of around 2,600 people that aimed to find out how demographic factors like ethnicity and age effected sleep. They found that age was negatively and linearly associated with all measures of sleep architecture, a frightening prospect if you spent your 20s and 30s partying late, studying late, and working late.

The resolution, says experts like Walker, is to get longer sleep, and ensure there’s nothing waking you up in the middle of the night, which may not always bring you out of sleep altogether, but just from deep sleep into a shallower stage of sleep.

Continue exploring this topic — Sleep — Sleep Still Works After Another Alzheimer’s Drug Fails In Clinical Trials

Continue exploring this topic — Neurology — The Brain Continues To Birth New Neurons Even At Ninety Years Young

Continue exploring this topic — Psychology — Shattering Temporal Boundaries of “The Self” Key to Living a Long Healthy Life