Of the many foreign policy challenges facing Donald Trump in his second term, fewer share the stark contrasts of the current deterioration of the already-none-existent relationship with North Korea.

It’s clear the only politician in America today who had both the potential to win the presidency and the potential to rejuvenate de-escalatory dialogue with the North was Trump, having come so close to making concrete improvements during his first term. However, it seems also clear that the DPRK has grown skeptical and hostile to the very idea of rejuvenating such talks, having seen more than one fail so significantly.

Nearly every American presidential administration has been content to inherit North Korea policy from its predecessor, change none of it, and hand it off to a successor. Efforts made by the Clinton Administration to reach out to then-leader Kim Jong-il stalled, and were eventually overtaken by other interests before Bush Jr. made them substantially worse. Obama made no alterations apart from a softer rhetorical tone and passed the policy to Trump who became the first president to enter the White House with Kim Jong-un in power.

Trump made a historic effort, resulting in the Panmunjom Declaration between the North and the South. But before this wave of goodwill and photo-ops could make any meaningful change in Washington DC, talks were soured by Trump’s National Security Advisor John Bolton. The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic changed the focus of both nations, and Trump passed America’s Korea policy to Biden who watched the DPRK develop hypersonic glide missiles for their nuclear weapons, sign a defense pact with Russia, and deploy special forces to help Russia reclaim territory captured by the Ukrainians.

Now Trump is in charge again, but there are some key differences. The first is that Trump has said, at least occasionally, that he learned a lesson from his first term that there were people, Bolton included, in his first cabinet that were not working on his behalf. Enter Pete Hegseth.

Trump’s unorthodox pick for Secretary of Defense defended Kim Jong-un and Trump’s attempts at negotiation in the lead-up to the first North Korea-US summit in Singapore in 2018. Hegseth defended Kim on Fox, describing him as “the guy who wants to meet with [former NBA star] Dennis Rodman and loves NBA basketball,” and adding that he “probably doesn’t love being the guy that has to murder his people all day long”.

So Trump has some cover from his Sect. of Defense, if Hegseth’s post is confirmed by the Senate. Contrastingly, Trump’s pick for Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, has called Kim Jong-un a “lunatic” who’s “mentally unstable,” so no help there.

Trump’s National Security Advisor is set to be Michael Waltz, as the position does not require Senate confirmation. Waltz is one of most vicious China hawks in Congress, a staunch guarantor of Israel’s genocide, and by extension, a staunch antagonist of Iran, so it’s safe to assume that his priorities will lie elsewhere. As to Waltz’s direct considerations of North Korea, he has yet to voice any.

In short, the biggest factor in US-North Korea relations will probably be Trump himself.

From Pyongyang’s standpoint

Unlike all previous attempts to negotiate with the Kim family, Pyongyang is in a fairly strong position. The regime’s continual development of its nuclear program has paid dividends, and now not only possess legitimate ICBMs, but allegedly also hypersonic glide missiles that are nuclear capable.

These more sophisticated weapons are the product not only of continual research and development, but an expanding industrial base that is now acting as supplier to not only China, the North’s long-time relation, but Russia, with whom the DPRK has developed a strategic partnership. This agreement just entered into force, and culminated with the deployment of a certain number of special forces to Russia to help retake the Kursk Oblast from Ukraine.

More crucially, it provided Pyongyang’s military with its first taste of combat in two generations, in the same year that the regime officially redesignated South Korea as an “enemy” nation.

Small pieces of commentary hint at the climate in Pyongyang over the idea of a second Trump Administration. State-run Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) issued a commentary five days after Trump made comments about having a personal relationship with Kim Jong-un in which it made clear that “the foreign policy of a state and personal feelings must be strictly distinguished”.

The commentary also came some days after State Department officials spoke in Seoul that “there is no change in the US policy toward the DPRK, including dialogue,” adding that the door to negotiations with the DPRK “is still open”.

The commentary dismisses the idea that Washington is the one who chooses whether the door is open or closed. It also clearly communicates that, in layman’s terms, North Korea has been burned by these dialogues, and has learned her lesson.

“There is no need to engage in dialogue in the first place, dialogue that is… an extension of confrontation,” the commentary read. “Through decades of relations with the United States, we have experienced acutely and fully what dialogue has brought us and what it has lost”.

In short, a lot; as Pyongyang sees it. A perfect summary of this comes from Keio University professor Isozaki Atsuhito, writing in The Diplomat.

“While the North Korea-United States summits were being held, North Korea suspended its nuclear missile tests and released detained US citizens. However, Kim did not attempt to hide his resentment at the lack of actual gains for his country, such as a partial lifting of economic sanctions or suspension of US-South Korea joint military exercises”.

Additionally, Isozaki quotes Kim from one of the leader’s final letters to Trump during this period.

“In this vein, I have done more than I can at this present stage, very responsively and practically, in order to keep the trust we have. However, what has Your Excellency done, and what am I to explain to my people about what has changed since we met?”

For all that Marco Rubio has seen to suggest that Kim is mentally unstable, the leader of a resurgent DPRK must feel that avoiding any negotiations with Trump’s second administration is sound logic.

Recently, and for the first time in 18 years, the UN sanctions on North Korea were not successfully reauthorized at the UN Security Council; credit going to their new strategic partner Moscow who exercised its veto. The Russian reasoning was that the sanctions were passed to prevent the North from acquiring nuclear weapons: something it had done long ago.

For the first time ever, Pyongyang can come to whatever table it likes, a strategy it has always employed—often successfully—but this time it’s doing so from a position of significant strength. The commentary acknowledged Trump had a special dispensation with Kim, but concluded that this should not be considered in future decisions.

“It is true that when Trump was president, he tried to reflect the personal friendship between the leaders and reflected it in the relations between the countries, but it did not bring about any real positive change,” it wrote. WaL

We Humbly Ask For Your Support—Follow the link here to see all the ways, monetary and non-monetary.

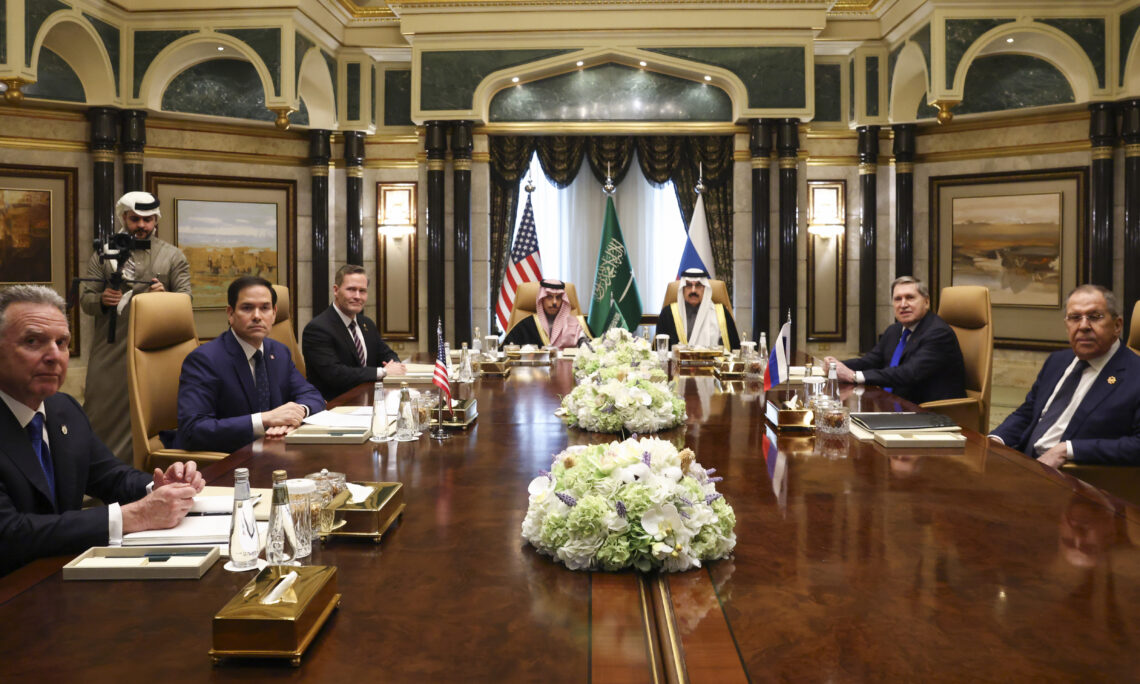

PICTURED ABOVE: Kim Jong-un arriving for a working lunch with Sect. of State Mike Pompeo in Pyongyang in 2018. PC: Office of the Secretary of State.