The gender division of labor among hunter-gatherers has been a topic of heated debate for decades, as much at least as the discussion of performance disparities between the sexes in organized sports and athletics.

A fascinating new study examining the versatility of movements among members of both sexes from 53 different hunter-gatherer societies shows how complex human locomotion, like climbing, running, swimming, and diving underwater, is widely practiced by men and women all over the globe—in places where the water is frigid, where the trees are tall, and where the Sun is roasting.

On the face of it, it’s a conclusion that seems to make sense intuitively—for the same reason that the 20th-century hypothesis of ‘Man the Hunter, Woman the Gatherer’ doesn’t seem to make sense: there’s far too much to do, and far too much at stake for such strict divisions of labor to exist.

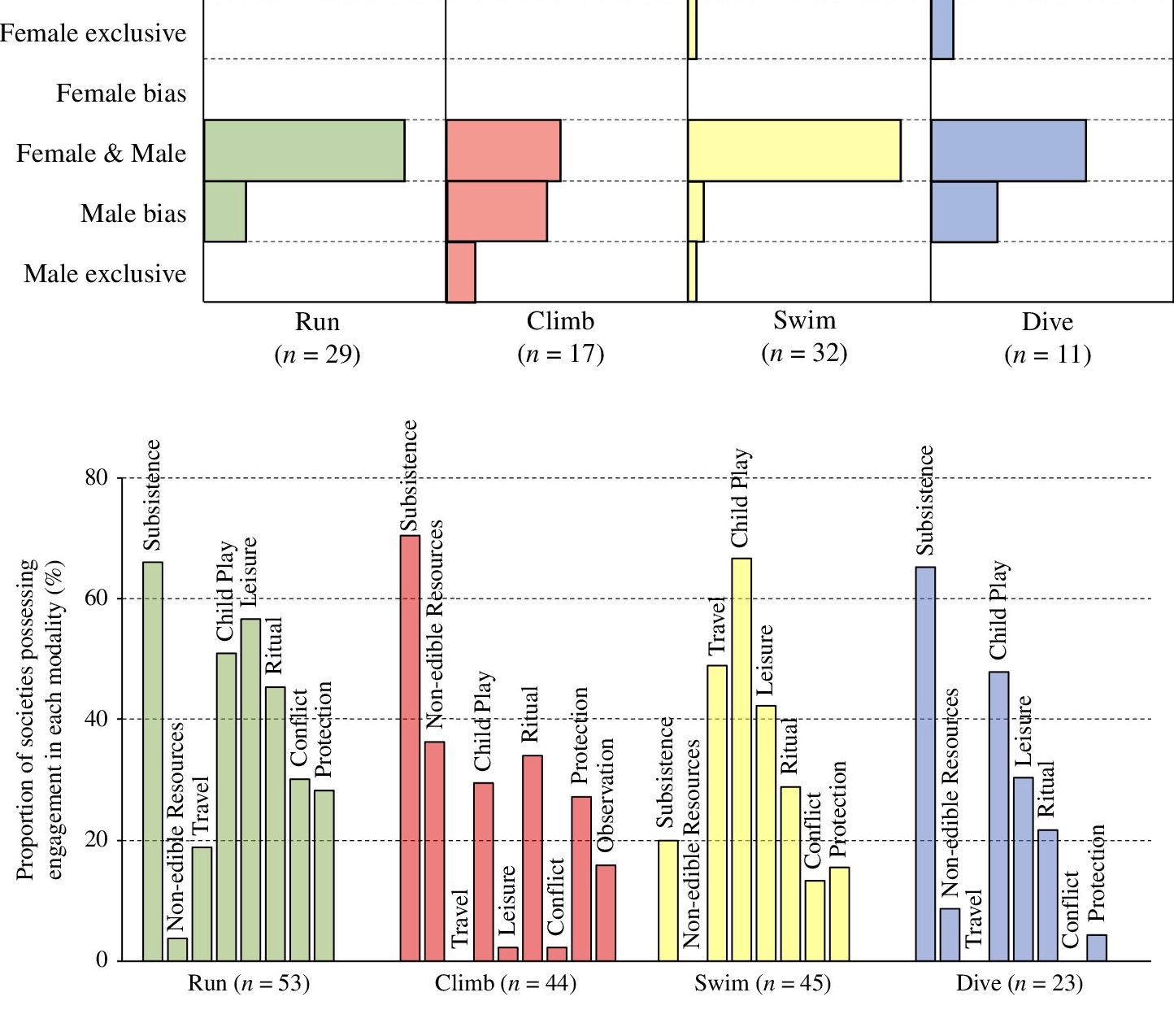

“A strict gender division in locomotor engagement was rare and, in most societies, men and women engaged in each of the locomotor modalities present,” conclude the authors of the paper, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society.

Beyond the conversation of mere gender differences, the study was fascinating in that it found most hunter-gatherer societies (42) partook in three or four of the patterns of movement, while only 11 engaged regularly in two or fewer. In other words, most societies climb, swim, and dive, along with running, often, and very rarely were the differences determined by the biome in which the society lived.

“Only in extreme cases does ecological context appear to constrain locomotor engagement,” wrote the study team from the Cambridge University Department of Archaeology. “The significance of locomotor versatility for subsistence, as well as for a range of other functional contexts, is clearly demonstrated,” adding that high-level proficiency in multiple forms of movement represents “a generalist repertoire achievable by the human phenotype generally rather than the realm of unique societies”.

There were some societies whose ecologies were so extreme that diving, for instance, could not be achieved. This included the Copper Inuit, who live in an environment where mean annual temperatures are -12°C, and mean annual water temps are about 5°C. Climbing wasn’t biased even a little towards forest biomes, and in fact the societies that climbed the most were those that live(d) in the desert. Furthermore, climbing proficiency was observed and documented in all societies apart from those dwelling at the two highest northern latitudes recorded.

While it’s true that the most proficient divers lived in the coastal biomes, over half the societies documented to swim and dive were inland, living more than 50 km from the coast.

So practically without regard to ecological niches, our ancestors routinely displayed aptitude towards climbing, running long distances, swimming, and even diving. And apart from a general male exclusivity to climbing, and a small male bias towards running and diving, both sexes partook in all four movements, which would today be considered aerobic exercise methods, equally.

Evolution as a guide

The study was informed by the accounts of ethnographers visiting and documenting the activity of hunter-gatherer societies and examining them for comment on a given society’s forms of locomotion. As such, many different behaviors formed the motive for the given activity, ranging from climbing to escape dangerous animals to diving so as to set up a duck decoy. Various rituals and leisure activities were also recorded, but in 60% or more of all societies, all 4 modes of movement were used for subsistence; either hunting or gathering.

Furthermore, and apart from climbing, children performed all of the movements whilst at play in 40% or more of societies, a key indicator of evolutionary selection for these activities since juvenile mammals play to practice the moments they rely on to survive when they reach adulthood, such as when leopard and lion cubs practice stalking, and juvenile monkeys play fight with one another.

Evolution can also act as a guide to where the smallest performance disparity between the sexes in the same activities will be.

In separate, unaffiliated research, Collin Carrol at Columbia University in New York examined how world records held by athletes in track and field can be used to estimate which physical movements humans evolved to specialize in. In Carrol’s study, he found that the greatest disparities in performance between men and women in track and field were found in the long jump event.

Carrol presents a hypothesis that the relatively small differences present between the male and female record holders in short and medium-distance running events suggest that sprinting and running in zone two were strongly selected for in the species as a whole, probably because humans relied on these speeds to escape dangerous animals and perhaps catch certain prey species.

By contrast, and because men have more testosterone, denser bones, a greater percentage of muscle mass, and a longer stride length, the disparities in the long jump show that humans likely never evolved to perform this movement out of necessity, and the large disparity in male and female performance reflects this by male individuals using their more powerful frames to their advantage.

It’s interesting too that the activity with the greatest bias towards men in the Cambridge study is climbing, an activity that takes significant and explosive upper body strength in the case of tree-climbing—much like the long jump, which was the activity with a largest performance disparity towards men. A bias towards men in running, by contrast, was found less than half as often as climbing.

“Our results suggest that, far from being the domain of only isolated specialists, habitual non-bipedal locomotion—often to high levels of proficiency and of primary economic importance—and indeed, locomotor versatility across each terrestrial, arboreal and aquatic domains, is widespread among human hunter-gatherers,” the authors write.

Sweat the difference

So, were primitive societies more egalitarian from the demands of physical movement? The Cambridge study relies on accounts by writers who may have only been recording movement habits as an afterthought, or at least not in the course of their primary goal of observation. A not small number of the accounts used date to the second half of the 19th century, when the ethnographers may have been writing through discriminatory or colonial lenses of observation.

As a result, the data must be considered with several grains of salt. However, looking at it all, an interesting trend emerges: almost all of the most active and proficient societies tended to have the smallest gender biases across activities. In other words, the more athletic the society, the less biased they tended to be.

These included the Mbau, from Fiji, the Timbira people of Northeast Brazil, the people of the Marshall Islands, the Manus in Papua New Guinea, the Tupinamba—also from Brazil, the Yurok Nation of northern California, and the Northern Paiutes. Other societies scored along similar lines but either a lack of one of the four locomotive types, or a lack of information, blocks us from being able to include them in this post-hoc list of egalitarian hunter-gatherers.

“In short, there may be something in this,” admitted George Brill, the lead author on the study, “but I would personally be tentative about concluding anything without further analysis, and even then, with the reasonably small sample, would still be cautious”.

That sample size, for example, includes stark few numbers of hunter-gatherers in Australia or mainland Asia, and perhaps if that number of were increased, this trend would flatten, or perhaps it would steepen. No one can say for certain. WaL

We Humbly Ask For Your Support—Follow the link here to see all the ways, monetary and non-monetary.

PICTURED ABOVE: The Manus People of the Admiralty Islands, Papua New Guinea. PC: William Robert Herbert, public domain.