DJA BIOSPHERE RESERVE, Cameroon. April 1st 2019. PICTURED: A chief of the Baka pygmies looks pensive in a forest camp. Photo credit: Alejpalacio. CC 4.0.

In southern Cameroon the communities of Baka pygmies, indigenous hunter-gatherers, have lived for millennia in and around dense rainforest of the Dja Biosphere Reserve. But in a tale as old as gunpowder, they’ve had all their ancestrally-inhabited lands given as concessions to extractive logging and mining companies.

With little to no legal representation inside their country, scientists from the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and Spanish NGO Zerca y Lejos, are working to help prove that not only do the Baka have ancestral land claims to their forest homes, but that allowing them to practice their traditional way of life could have profoundly beneficial impacts on biodiversity conservation, and sustainable, long-term use of natural resources.

Starting in the early 20th century, following independence from France, the Cameroonian government legislated the Baka pygmies out of their forest villages and into roadside habitations next to Bantu-speaking communities, in order to bring them closer to society.

Following the 1994 Forestry Law, which delegated how forest resources and ownership are divided, the Baka were left without domestic mechanisms to demonstrate ownership of their lands.

“This is a very tricky topic,” surmises Julia E. Fa, Professor of Biodiversity and Human Development at Britain’s Manchester Metropolitan University and senior research associate at CIFOR. “Overall, there is a good disposition from the government to try and come closer to a solution or resolution to potential conflicts between territories that the Baka pygmies are using, and the territories that other people are taking over — extractive industries or conservation”.

Fa was part of a large study published in Nature that used a technique called participatory mapping surveys, which is a method of demonstrating ownership of land through use of it, an internationally-recognized claim in indigenous human rights law.

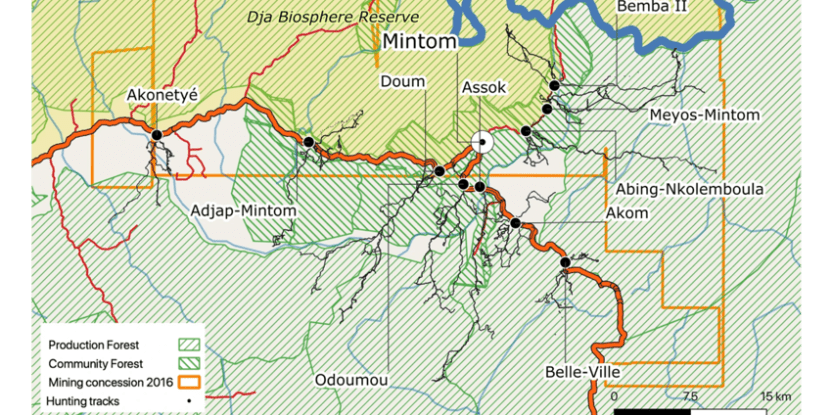

PICTURED: A map of the 10 Baka villages involved, their allocated communal forests, the biosphere, and the logging and mining concessions. Photo credit: Fa et al.

A run through the jungle

In 2017 and 2018, Fa and her team sought to involve the pygmies in a series of workshops that showed them how to read and use maps to identify rivers, hunting trails, cultural sites, forest hunting camps used on multi-day hunts, and other objects of interest in their hunting traditions.

“Participatory mapping is something that’s been used by a large number of researchers as well as communities to actually reinforce their rights,” explained Fa in an interview with World at Large.

“If you look at, for example, Rainforest Foundation UK or Forest Peoples Program, they are actively using participatory mapping as a way of having on-paper maps, that they can then show the government and say; ‘look ,these are the areas these people are using, and they must be respected’”.

Under the principle of free, prior, and informed consent, with every participating pygmy understanding they can leave or cease their involvement at any time, over 400 community members attended the workshops, and agreed to wear Garmin GPS wrist transponders during their hunts, which would broadcast their position every 90 minutes.

Fa explained the workshops were always fun, full of food, drink, and laughter.

Recording their activities and familiarity with the forest would make a strong case for creating some kind of traditional owner or stewardship roles for the Baka. Unfortunately, while the method is excellent for collecting data and evidence, the translation into land-rights or land-use cases won, is rare.

PICTURED: A ‘pygmy’ mother and her kids from the DRC, from the Aka, or Bakaya group; closely related to the Baka. Photo credit: Max Chiswick. CC 4.0.

Pygmies: iconic hunter-gatherers

While the term “pygmy” is of colonial origin and derogatory in nature, there is no universally-utilized alternative. Rather it is simply a method of identifying a diverse group of rainforest-dwelling hunter gatherers whose ancestral habitat is the dense jungle of the Congo Basin.

The Baka collect most of their food from hunting, but following their translocation to the roadsides to live next to Bantu-speaking farming communities, they’ve adopted certain subsistence agricultural crops to supplement their meat-heavy diet.

Nevertheless, pygmies across the Congo Basin fare poorly when taken out of their traditional way of life, their mental and physical well-being diminishing with the introduction of modern diet and lifestyle factors that also plague many of us, such as alcoholism, smoking, sedentary lifestyles, and overconsumption of simple carbs and sugar.

“Even though the Cameroonian government has given these communities what we call ‘communal forests,’ they’re definitely not sufficient enough to be able to provide what they need in their lives,” says Fa.

Furthermore, evidence that logging has disrupted the Baka’s livelihoods is well-documented, and a large influx of logging laborers and an expansion of the local bushmeat trade, which is putting pressure on game animals, will make it even more difficult for Baka communities to continue their ancestral lifestyles.

“If you compare the peoples of the Amazon basin with what’s happening in Africa, to people in the Congo Basin, we have night and day comparisons”.

PICTURED: Villagers pose with their bows circa. 1911, in northeast Congo.

Results and International law

After a month of monitoring, Baka participants embarked on 1,958 hunts, averaging 30 kilometers in travel time, but sometimes as much as 90.

The data revealed that many villages’ hunting grounds over-lapped each other, despite the fact that at nearly 2,000 square kilometers, the territory was twice the size of Hong Kong. For those in the know, it’s not a surprise.

In her team’s study, Fa references another paper that showed how indigenous people “manage or have tenure rights over at least ~38 million km2 in 87 countries or politically distinct areas on all inhabited continents,” amounting to a quarter of all land surface, and 40% of all protected areas and intact ecological zones.

So much ground to cover lead these researchers to conclude that it should be an imperative for global conservation to involve indigenous peoples in stewardship roles, and that to do so would “yield significant benefits for conservation of ecologically valuable landscapes, ecosystems and genes for future generations”.

The United States’ Declaration of Independence often makes reference to what was a prevailing theory among the work of British philosophers like John Locke and David Hume, the idea of natural rights. Men have endowed in them by their creator, or inherent within them through their very nature, certain natural rights which are not given at the pleasure of their governments.

Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, which Cameroon is a party to, expresses in much the same way the Founders did, that indigenous people have rights to land onto, and into which, they have inseparably mixed their culture; which they “occupy or otherwise use,” as 169 says.

“What we show in the study that we’ve done, is that these peoples are not, in a way respected, in the sense that they haven’t been given land that is, in fact theirs,” says Fa, echoing the high-minded convictions of the convention.

Researchers and legal scholars generally agree that indigenous rights to land supersede rights to land granted by government concessions, since they are derived from the ancestral occupation and traditional use of lands and resources; i.e., they were there first.

“There’s a lot more work to be done, and what we wanted to do in our study is show that this is an issue that’s actually affecting these Baka communities, and that we should pay attention to it”.

“We are looking towards in the next few months to go back to Cameroon and actually continue the project,” says Fa. “We do need to get the government to approve these territories and make sure these peoples do have the right to the land which they’re using, because at the end of the day, anyone can come in and say, ‘well, you can’t come here, this is not an area for you to hunt”.