A pair of lost cities in the highlands of Uzbekistan recently found by archaeologists using lidar demonstrate that the bounty of the Silk Road trade was so lucrative, it allowed urban populations to flourish without agriculture to support them.

Tugunbulak and Tashbulak were two mountain settlements that flourished between the 8th and 11th centuries CE nominally under the control of a Turkic state known as the Qarakhanids that held influence over a slice of Central Asia spanning from the Aral Sea to the Taklamakan Desert.

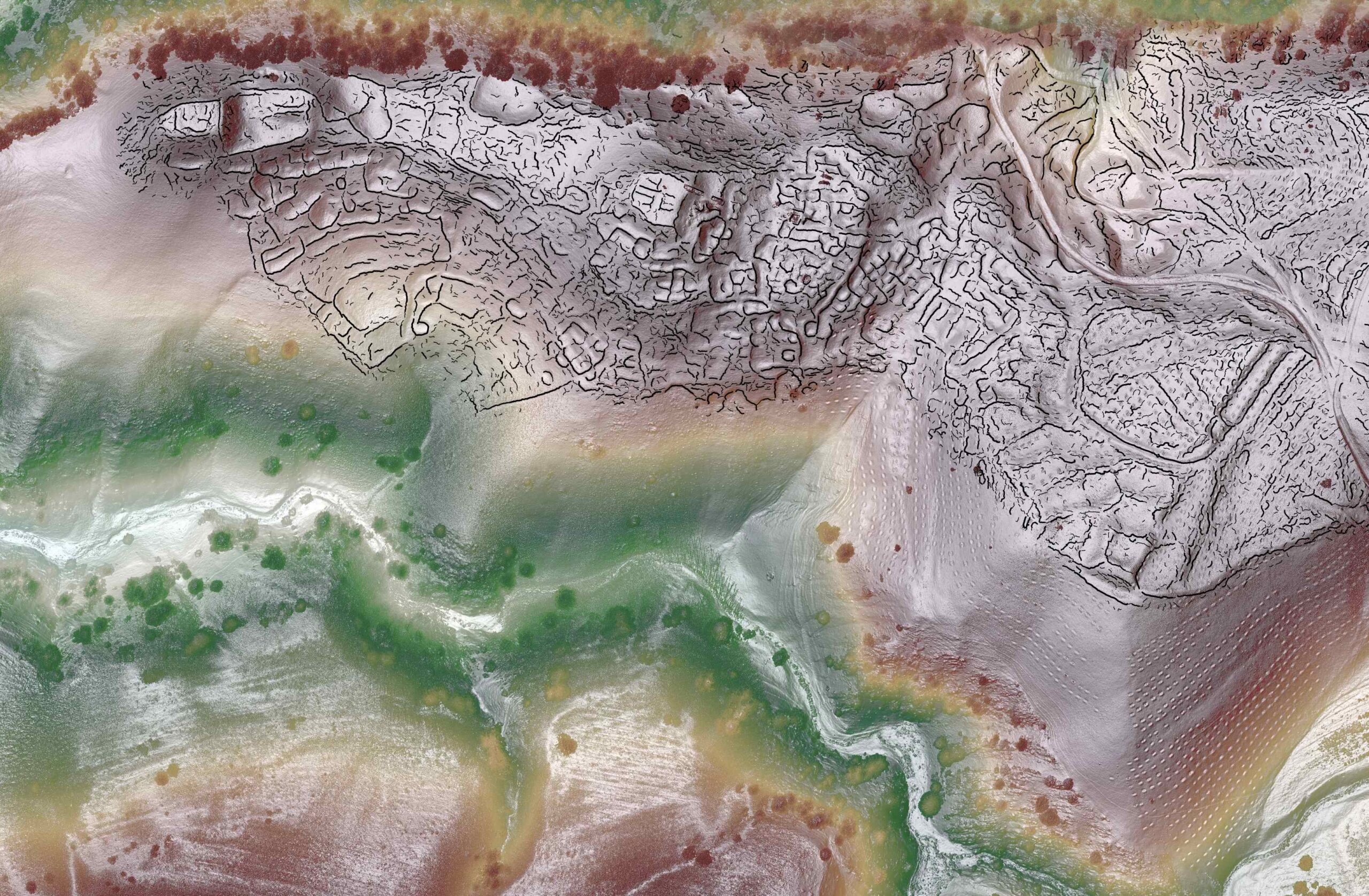

Along with his colleagues, Michael Frachetti, lead author of the paper on the discovery and lead excavator on the sites since 2011 carried out the first lidar survey in the history of Central Asian archaeology to make the discovery. Lidar stands for Light detection and ranging and uses laser-based technology to map landscapes from the air. It’s one of the most consequential technological innovations in the history of archaeology and has been used all throughout the world to find evidence of past habitation where today only nature remains.

Typically, lidar is used when trees block the view of any eyes looking down upon a landscape, but archaeologists speaking with Science remarked with astonishment how nuanced the lidar survey’s topographical readings were, and how much more they revealed compared to looking down from above on what is essentially an open field.

Tugunbulak occupies approximately 120 hectares (1.2 sq. kilometers) and shows evidence of over 300 unique structures, which vary in size from 30 to 4,300 sq. meters. More specifically, the researchers identified watchtowers connected with walls along a ridge line, evidence of terracing, and a central fortress surrounded by walls made of stone and mudbrick.

Tashbulak, meanwhile, occupies 12–15 hectares (0.12–0.15 km2). Frachetti and colleagues note that even the smaller city follows urban planning similar to concurrent cities in medieval Central Asia, namely it includes a central citadel made of an elevated mound surrounded by dense architecture and walled fortifications. They suggest that there are at least 98 visible habitations, which share a similar shape and size to those in Tugunbulak, and hypothesize that both cities were built to exploit the surrounding mountain terrain for defense as well as the abundant ores and pastures the highland region provides.

Both sites sit at or above 6,000 feet (2,000 meters) above sea level. Even today with all of humanity’s power to move and shape the landscape, only 3% of the global population dwells at that elevation or higher.

“High-altitude urban sites are extraordinarily rare in the archaeological record because of a unique set of landscape challenges and technological demands that must be overcome for people to form large communities in mountainous areas,” writes Zachary W. Silvia, a professor at Brown University’s the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, who wasn’t involved in the study.

A Tale of Two Cities and the Wealth of Nations

Discovered in 2011 and 2015, Tashbulak and Tugunbulak sit along the famous collection of overland trade connections that linked East and West popularized in the 20th century by the name of the Silk Road(s). Rather than being a single highway, the Silk Road was instead an intricate, human-powered commercial network that allowed Rome to trade glass and cotton for China’s silk without one civilization ever needing to visit the other.

A variety of ethnic groups, kingdoms, and oasis cities linked these disparate powerhouses of their day, the fortunes of whom rose and fell with the trade along the dozens of individual routes that made up the Silk Road. Famous Central Asian cities like Bukhara, Samarkand, Merv, Kashgar, and Khiva flourished off this trade, but were located on planes or lowlands with abundant water supplies.

Nestled in a valley in the Mal’guzar highland range of southeastern Uzbekistan, a northern offshoot of the formidable Pamir Mountains, Tashbulak and Tugunbulak are far from being as conveniently located, and despite being far from any suitable land to practice agriculture, Tugunbulak, which is over half the size of Samarkand from the same period, could have housed as many as 5,000 residents with the only source of food being pastured animals or what could be imported.

The evidence that pastoralists inhabited the city is convincing. Coupled with the impressive fortifications, artifacts recovered during digs in the city suggest that Mal’guzar was beyond the cultures of any then-ruling states, and existed as a somewhat separate entity—which in Central Asia almost always means nomadic. No sub-urbanism seems to have developed beyond the scope of Tugunbulak’s walls, reinforcing that the inhabitants dwelt in yurts or felt tents if no room could be found in the city.

Excavations in the city revealed the presence of iron ore foundries with domed furnaces that likely produced steel from the wealth of iron veins in the surrounding hills. The city seems to have been a fortified center of metallurgy, producing weapons, farming implements, and equestrian tackle for nearby societies and spending their revenues on imports to sustain their mountain living.

As was the case with many cities along the Silk Road, a shift in commonly used routes because of danger or environmental change, the fall in demand for a product thousands of miles away, or the onset of war, might dry up the life-sustaining trade in remarkably short time, and the course of the Silk Roads are littered with results of these changes in fortune, something that Tashbulak and Tugunbulak must have fallen victim to.

“Frachetti and colleagues’ work provides an immense contribution to the study of medieval urbanism in Central Asia, as well as to the poorly understood phenomenon of dense settlements at high altitudes,” Silva adds. “Future work will certainly reveal the economic and social effect that these sites wielded over contemporary cities across these medieval Silk Roads”. WaL

We Humbly Ask For Your Support—Follow the link here to see all the ways, monetary and non-monetary.

PICTURED ABOVE: The mound of Tugunbulak looking westward. PC: Michael Frachetti.