Officials with the China Manned Space Engineering Office (CMSEO), who rarely comment on the details of future space missions, have nevertheless announced that China is aiming to put astronauts on the moon in 2029.

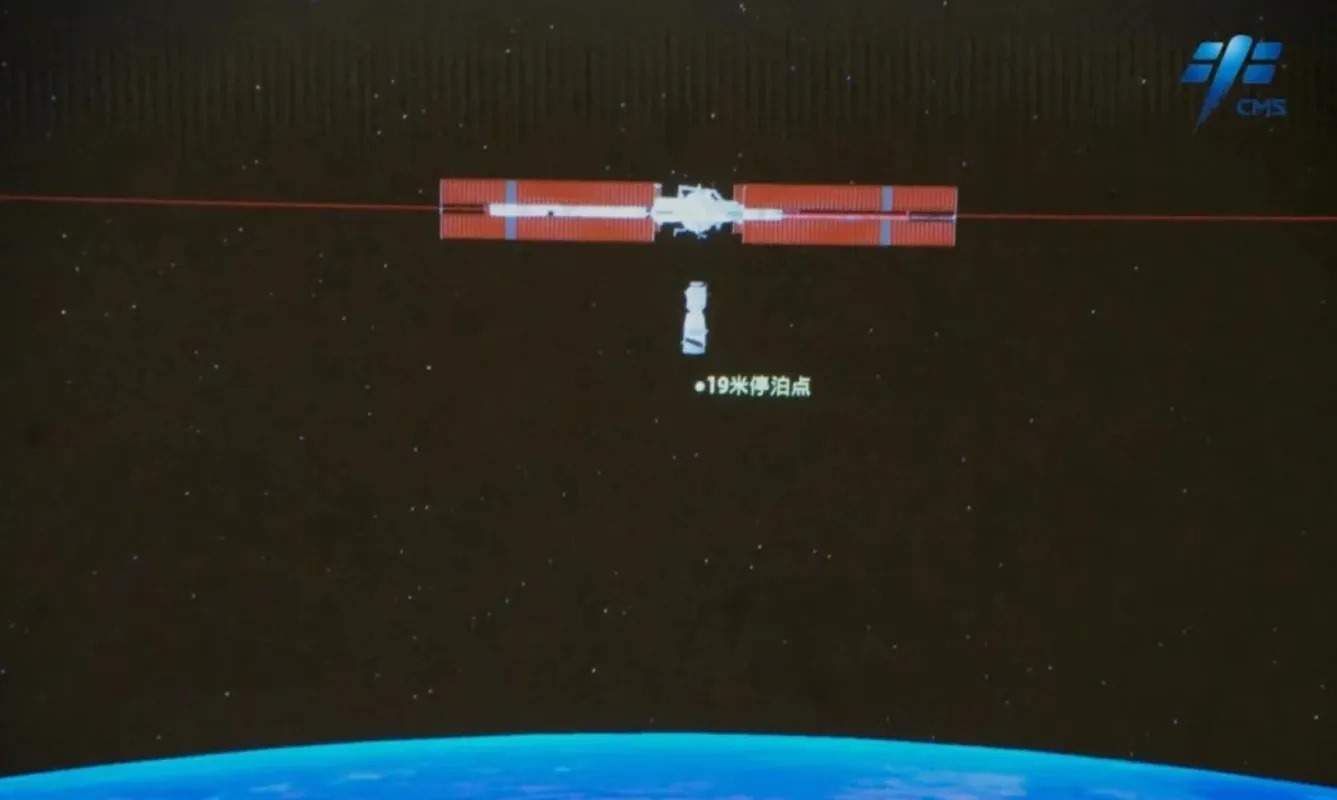

The statement came with the announcement of the crew to ride the Shenzhou-18 mission to China’s very own space station, called the Tiangong.

“The program development for major flight products, including the Long March 10 rocket, the Mengzhou crew spacecraft, the lunar lander Lanyue and the lunar landing suits, are all complete,” said Lin Xiqiang, deputy director of CMSEO. “Their prototype production and tests are in full swing. Crew lunar rover and lunar surface payloads solicited from the public are under selection”.

According to their plans, the CMSEO will use two variants of their space program’s rockets, called the Long March, to send Mengzhou, Lanyue, and three astronauts into lunar orbit, where they will perform several orbital maneuvers in advance of landing the Lanyue with two of the three crew members. They will stay there for 6 hours, sticking a flag in the regolith one presumes, before rejoining their colleagues on the craft above.

Despite all the largest hardware items having been completed, there remains the need to gather and test the more hands-on elements of the mission, such as rover and lunar surface suits, and train on all the space craft, their maneuvers, including standard and emergency maneuvers, how to navigate a lander onto the surface, and how to work in one-sixth Earth’s gravity. Still, the belief is that 2029 is a feasible date.

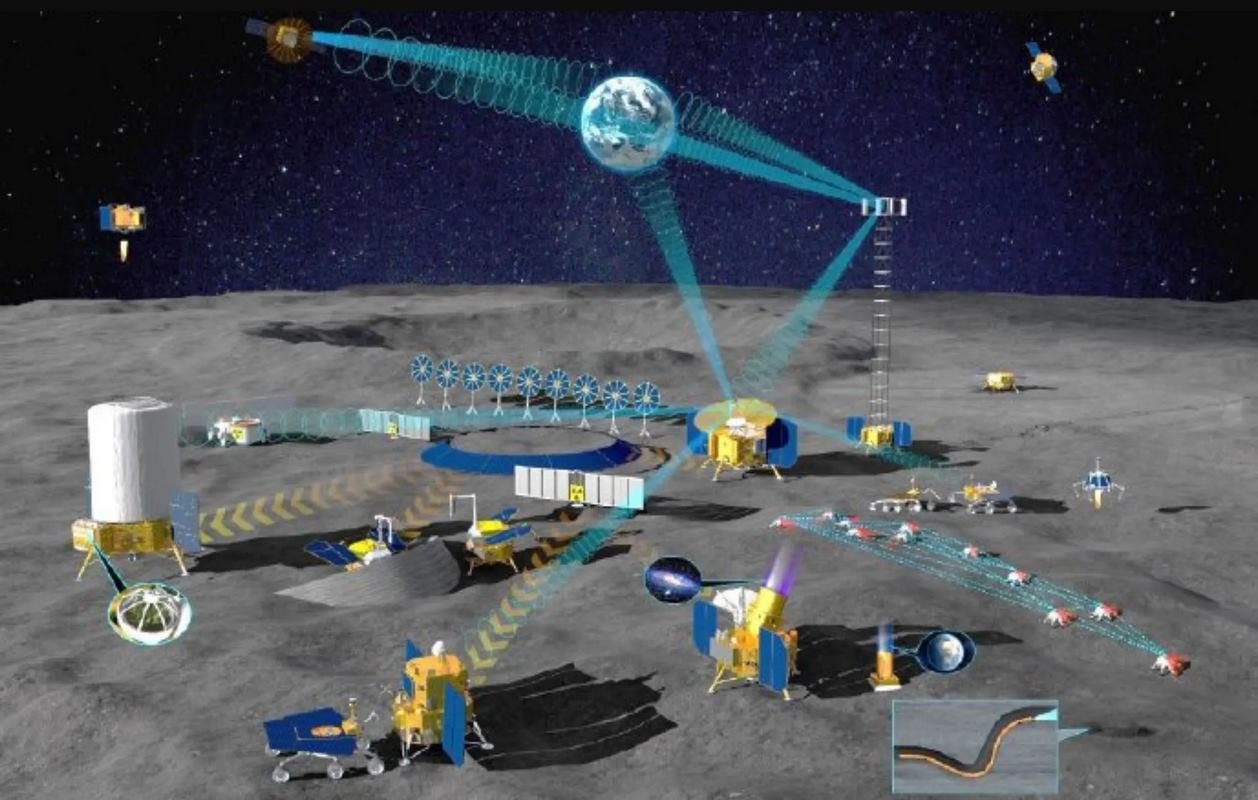

The mission is part of China’s plan to establish a semi-permanent presence on the moon which they have opened up for international collaboration, the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). According to Space News’ Andrew Jones, this will include a suite of robots and a constellation of satellites and orbiters around the moon to assist in research.

The ILRS is believed to be something of an alternative to the Artemis Accords, the United States’ official policy, collaboration, and development program that invites nations to sign on to a set of principles governing the use of space.

Friendly competition

WaL reported last year that some scientists and policymakers see the Artemis Accords as planting the first seed of a kind of global human vision for space colonization; something like a UN for the stars. More cynical ones would probably see it more like NATO, namely a way for the US to ensconce allied economies into a muscular unipolar organization for the exploitation of the solar system. As above, so below.

In either case, and similar to the Belt and Road Initiative, the Chinese have attracted many launch-capable nations outside the NATO blanket to sign the ILRS, including Pakistan, United Arab Emirates, Russia, Malaysia, and the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization, which also includes Turkey, Thailand, Peru, Iran, Bangladesh, and Mongolia. Nicaragua also recently joined.

The Artemis Lunar landing, which had originally been slated for 2025, was recently announced as being unlikely to happen before 2027, following a report from the Government Accountability Office.

The GAO report, released November 30th, found that neither the newest space suits nor the Human Landing System (HLS) in development by SpaceX, are ready for a 2026 launch.

“We found that if the HLS development takes as many months as NASA major projects do, on average, the Artemis III mission would likely occur in early 2027,” the report stated, pointing to an ambitious schedule, delayed progress on its development to date, and significant technical work owing to the challenges of human spaceflight.

The Chinese Manned Space Agency (CMSA) also have a long road ahead of them, as they haven’t even received plans for a lunar rover, despite announcing in May 2023 that they were seeking concepts from the Chinese market.

The rest of the Chinese space program is going swimmingly, with April 25th witnessing the arrival of the Shenzhou-18 mission which brought 90 experiments and 6 astronauts to the Tiangong space station. Multiple lunar modules are on schedule for launches in 2027 and 2028, including Chang’e-8 which will aims to test 3D printing technology for the purpose of printing lunar habitation. WaL

We Humbly Ask For Your Support—Follow the link here to see all the ways, monetary and non-monetary.

PICTURED ABOVE: A concept drawing of the ILRS footprint on the moon. PC: China DSEL.