Large quotations in this story were only possible because of The Intercept’s publishing of a secret cable. To read their full report, and the appropriate context and background to this story, click here.

34 days before the April 10th no-confidence motion that saw Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan removed from office, a State Department bureau chief pressured the government to do just that, threatening “isolation” but adding that “all will be forgiven” if a no-confidence were to succeed.

This was shown in a cable marked “Secret” that was leaked to the investigative journal The Intercept by an anonymous source in the Pakistani military. The existence of such a cable has long been referenced, cited, and dismissed by the parties in the swirling political maelstrom that followed Khan’s dismissal, and by authorities at the State Department.

Much of the following material comes from the report at The Intercept, written by Ryan Grim and Murtaza Hussain, who made extensive efforts to try and verify the contents of the cable. Circumstantial evidence regarding statements made in the document suggests its veracity.

The cable is written by Pakistan’s Ambassador to the United States, Asad Majeed Khan, following a March 7th, 2022 meeting he had with Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, Donald Lu.

This was the date given in a report by the Pakistani news outlet Dawn back in October of 2022. Dawn claimed to have seen the cable, which they refer to as a “cipher”. Imran Khan in a speech on March 27th, held up a letter saying it contained evidence of a “foreign conspiracy” to topple his government, before naming the United States outrightly in following appearances. Since then the US State Department has repeatedly dismissed the allegations as “misinformation and disinformation”.

Regarding the contents of this most recent cable, Department spokesman Matthew Miller said when asked about the report, that “…what they [the contents of the cable] show is the United States Government expressing concern about the policy choices that the prime minister was taking,” and that it was “not in any way the United States Government expressing a preference on who the leadership of Pakistan ought to be”.

That’s not really correct, as will be seen below.

The language used by Ass. Sect. Donald Lu, however, is typical diplomatic vagueness, and contains all the uncertain terms and veiled intentions necessary to conceal any real misconduct.

Veiled threats

Ambassador Asad Khan opens the cipher with Lu’s and the White House’s chief position that “people here [the US] and in Europe are quite concerned about why Pakistan is taking such an aggressively neutral position (on Ukraine), if such a position is even possible. It does not seem such a neutral stand to us”.

Lu would go on to detail that the White House’s problem didn’t stem from Pakistan’s abstention on the United Nation’s General Assembly vote condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but it was Prime Minister Imran Khan’s trip to Moscow to discuss economic ties.

“I drew his attention to the fact that the Prime Minister clearly regretted the situation while being in Moscow and had hoped for diplomacy to work,” Ambassador Khan wrote in the cipher, published on The Intercept. “The Prime Minister’s visit, I stressed, was purely in the bilateral context and should not be seen either as a condonation or endorsement of Russia’s action against Ukraine”.

He added that the visit had been planned years in advance and that other Western leaders were traveling to Moscow around the same time. But Lu was not having it, with the bureau chief saying that he believed the decision was purely the Prime Minister’s personal policy, one which reflected political turmoil in Islamabad.

“I replied that this was not a correct reading of the situation as Pakistan’s position on Ukraine was a result of intense interagency consultations,” Amb. Khan writes.

“I think if the no-confidence vote against the Prime Minister succeeds, all will be forgiven in Washington because the Russia visit is being looked at as a decision by the Prime Minister,” Lu said, according to the document. “Otherwise, I think it will be tough going ahead”.

What does tough going mean? Lu only went as far as to suggest that it was his thinking that “isolation of the Prime Minister will become very strong from Europe and the United States”.

Was that an open threat? Could it be considered one when combined with the language that “all will be forgiven” if the “no-confidence vote against the Prime Minister succeeds?” Or was Lu simply stating what he envisioned would be the response based on the political climate?

The pressure intensified when at the conclusion of the conversation, Amb. Khan says that he hopes the misunderstanding regarding the Prime Minister’s visit to Moscow would be quickly left behind. Lu replied that he believed things were too far gone.

“I would argue that it has already created a dent in the relationship from our perspective,” said the Secretary. “Let us wait for a few days to see whether the political situation changes, which would mean that we would not have a big disagreement about this issue and the dent would go away very quickly”.

This was the second reference to possible political change, one which included the carrot and stick—that the dent would go away very quickly.

Aftermath

One day later, on March 8th, the parliament took a major step towards organizing the no-confidence vote, which succeeded on April 10th and threw the country into turmoil. Always at risk of influence from the nation’s powerful military establishment, Pakistani politics is extremely messy and often corrupt.

Huge protests followed in the wake of Khan’s dismissal, paralyzing parts of the country’s institutions and economy. The military began a crackdown on civil society and publishing organizations, and a general decline in democratic rights settled over the major cities like a pall of smoke. Several prominent journalists, The Intercept reports, were killed under difficult-to-explain circumstances.

In November, a month after Dawn’s report of the existence of the cable, Khan was subject to an assassination attempt that wounded him and killed one of his supporters.

Two policy alignments followed in the wake of the Lu-Khan meeting. The first was a statement on April 8th by then-Pakistan army chief Qamar Bajwa condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and seemingly reversing the Prime Minister’s position of neutrality.

The second was a lucrative August 2022 agreement of a defense pact with the US of an unspecified amount, covering “joint exercises, operations, training, basing and equipment,” to replace a 15-year military agreement that expired in 2020.

Last week, Imran Khan was arrested after being found guilty of profiteering off official diplomatic gifts by selling them at secret auctions. The court ordered his arrest from his Lahore home, to serve 3 years in prison for corruption, and placed a 5-year ban on his political activities.

Used and abused

Ever since the large post-war political scandals in America like Iran-Contra and Watergate, government documentation has gradually become softer and softer in its language, all for the purpose of creating ambiguity if a leak should occur. Secretary Lu was never going to say that Washington wants regime change; the extension of his beliefs of the coming isolation was as far as most officials would ever go in expressing true policy proposals of that nature.

Whether or not this was a slightly veiled threat of isolation, the cable reveals something else that should concern Americans: how unilateral a bilateral relationship with the US can feel sometimes. Ambassador Khan reported to Lu the general consensus among the cabinet that the US was treating Pakistan unfairly; expecting full compliance with the Biden Administration’s policies, while giving the cold shoulder to any that Imran Khan’s might have: including in regards to Afghanistan.

“I told Don that just like him, I would also convey our perspective in a forthright manner,” Khan wrote. “I said that over the past one year, we had been consistently sensing reluctance on the part of the U.S. leadership to engage with our leadership. This reluctance had created a perception in Pakistan that we were being ignored and even taken for granted. There was also a feeling that while the U.S. expected Pakistan’s support on all issues that were important to the U.S., it did not reciprocate and we do not see much U.S. support on issues of concern for Pakistan”.

“I also told Don,” he continued, “that Pakistan was worried of how the Ukraine crisis would play out in the context of Afghanistan. We had paid a very high price due to the long-term impact of this conflict,” he wrote. Indeed, Pakistan was subjected to continuous violence from the Taliban insurgency in response to the county allowing the US government total freedom when operating militarily in the border region between the two countries. US Reaper drones routinely prowled that border area and killed hundreds of innocent Pakistanis.

“Our priority was to have peace and stability in Afghanistan, for which it was imperative to have cooperation and coordination with all major powers, including Russia. From this perspective as well, keeping the channels of communication open was essential. This factor was also dictating our position on the Ukraine crisis,” wrote the Ambassador, who wasn’t done saying his piece.

“Pakistan valued continued high-level engagement and for this reason the Foreign Minister sought to speak with Secretary [of State] Blinken to personally explain Pakistan’s position and perspective on the Ukraine crisis. The call has not materialized yet.”

He further brought up what his administration viewed as an unfair dichotomy between how the US responded to India’s abstention of the UNGA vote on the Ukraine war, which was softer, compared to Pakistan’s which was harsher.

“Don” replied little to any of this, and simply stated that he would take Khan and his cabinet’s positions back to his leadership.

Imran Khan’s opposition in Pakistan and the US State Department had both said that claims of foreign coercion or plotting to oust the man from the Prime Ministership were false. In light of the cable’s declassification, the State Department has simply said that its contents represent an official expressing the Department’s concern, without claiming the cable was fabricated; meaning they don’t believe that it was.

If that’s true, then what’s said by Lu must be looked at critically: based on all the concerns that Ambassador Khan details, it’s clear cooperation with the US was incredibly important for Pakistan’s cabinet in late winter 2022, and it’s also clear that unless a no-confidence vote is successful, and a political situation changes, Pakistan could have been “isolated” from the US and Europe. That’s clear coercion, and also clearly represents a conscious preference in political leadership in South Asia. WaL

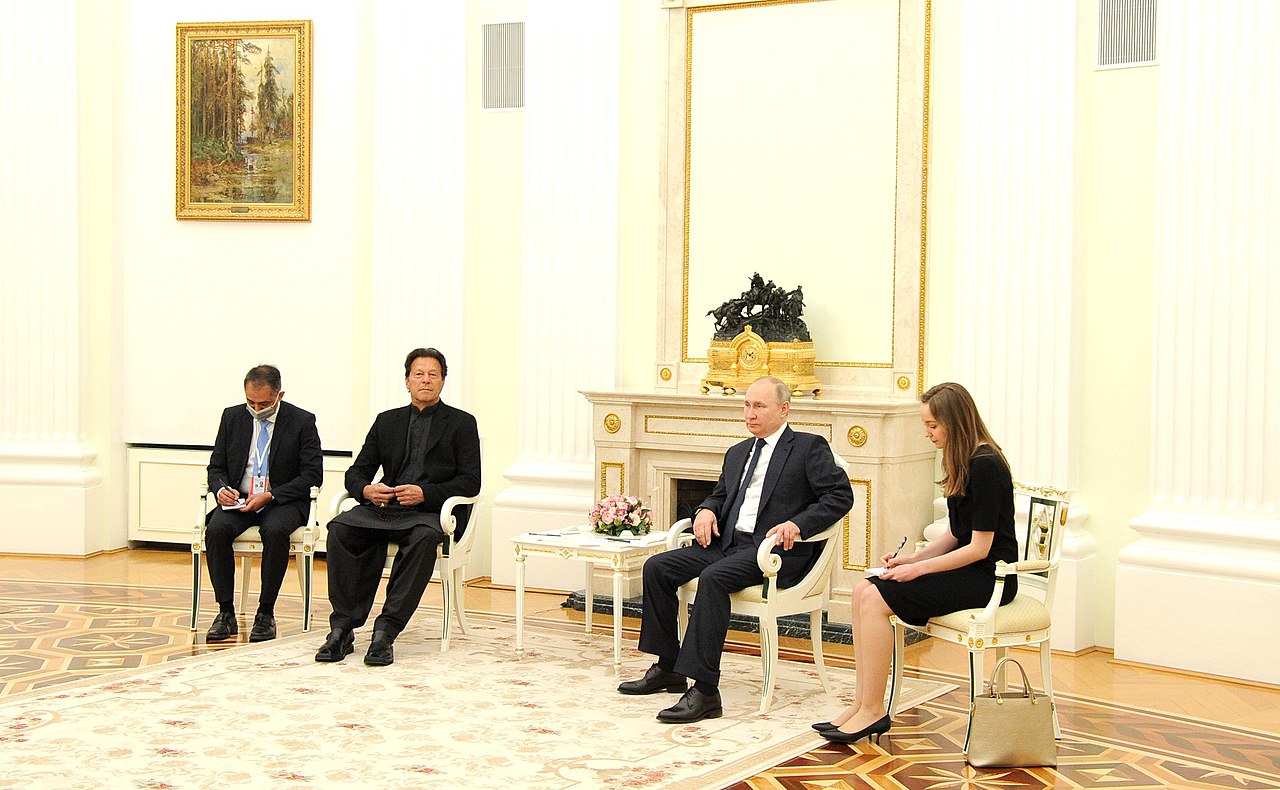

PICTURED ABOVE: Vladimir Putin and Imran Khan meeting in 2022, which may have led to Khan’s removal by the US. PC: Kremlin.ru CC 4.0.