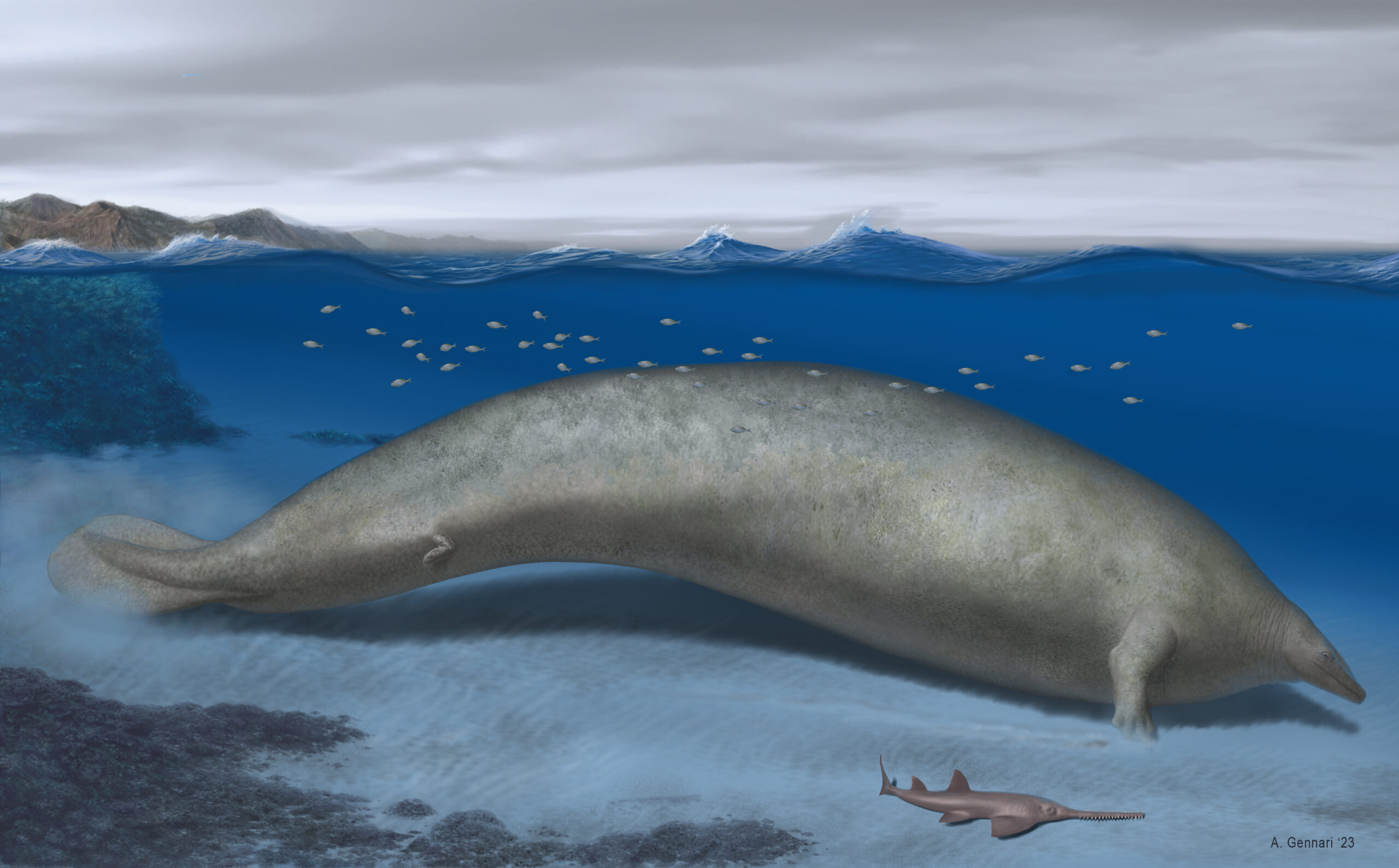

Peru isn’t typically associated with ocean habitat, containing as it does the Andes and the Amazon. However, a beast of colossal proportion has been unearthed there that could change our understanding of marine mammals forever.

Perucetus colossus, or the Peruvian colossal whale, is an ancient species of whale now thought to be one of if not the largest and heaviest animal to ever exist, reports a study published in Nature.

Estimates of its size and weight, based on a partial skeleton, rival those of the blue whale, which was previously thought to be the heaviest animal ever to exist. The findings suggest that the trend towards gigantism in marine mammals, and possibly the development of blubber, may have begun earlier than previously thought.

“For the skeletal and body mass estimations, we took a lot of uncertainty into account, and provided very conservative estimates, so I am very confident about the fact that Perucetus‘ mass was in the ballpark of that of the blue whale,” corresponding author Dr. Eli Amson, the curator of fossils and mammals at the State Museum of Natural History in Stuttgart.

The fossil record of cetaceans, a suborder of mammals that includes dolphins, whales, and porpoises, is of great importance when documenting the evolutionary history of mammalian life when some terrestrial animals were returning to the ocean. Previous records have identified adaptations to an aquatic lifestyle, which include a trend towards gigantism and an associated increase in body mass.

Dr. Amson and his colleagues published their paper on the remains of a basilosaurid whale discovered in southern Peru which lived in shallow seas during the Eocene epoch, around 55-33 million years ago.

The remains include 13 vertebrae, 4 ribs, and 1 hip bone. Predictive modeling would render the skeletal mass of the animal 2–3 times that of a 25-meter-long blue whale, They estimated that P. colossus had a body mass between 85 and 340 metric tonnes, making it the heaviest animal ever to exist.

One massive mystery

The bones of P. colossus are “extremely unusual”.

“The cross-section of a mammalian bone commonly looks like a baguette in terms of having a hard and solid crust (compact bone) that surrounds a spongy interior (trabecular bone),” write J. G. M. Thewissen and David A. Waugh from the Department of Anatomy and

Neurobiology, Northeast Ohio Medical University, who were not involved in the study.

“The proportions of crust and interior vary according to the animal’s need. Hippopotamuses, for example, need to walk fully submerged on riverbeds, so their bones have a lot of compact bone that makes their skeletons heavy, Perucetus colossus is on the hippo end of the

scale, with bones mostly or solely made of compact bone”.

This whale isn’t just on the hippo end of the scale, but its bones are almost wood-like in their density, as Dr. Amson explains.

“Pachyosteosclerosis is the combination of two processes that have the same result, an increase of bone mass,” he told WaL. “These are adaptations, not [diseases] found in shallow diving animals such as manatees. Pachyostosis is the deposition of additional bone tissue on the surface of bones, giving them a bloated appearance. Osteosclerosis is the increasing of compactness of the bones, by filling of inner cavities with even more bone”.

In short, the giant whale was making its bones denser inside and out. This is in complete contrast to modern whales, whose skeletons are actually on the lighter side of the mammalian bone density scale.

Trusting that evolution rarely occurs in a vacuum, Thewissen and Waugh hypothesize that P. colossus and its cousins may represent the progenitors of blubber seen in marine mammals today. The oceans were cooling during their existence, and modern whales possessing of the heaviest bone structures, such as the sei and bowhead whales, maintain neutral buoyancy with thick layers of fat called blubber, absent in other whales like blue, fin, and sperm whales.

“The head of Perucetus is a complete mystery. In the paper, we have only listed speculative hypotheses regarding its diet. The bone mass increase (osteosclerosis and/or pachyostosis) in marine mammals is usually associated with a herbivorous diet, said Dr. Amosn. “But this would be a complete first for cetaceans, so we deem it unlikely. My personal favourite is that it was a scavenger, feeding on underwater carcasses of some other large animal”.

PICTURED ABOVE: Perucetus colossus. PC: Alberto Gennari.