In a fascinating star system 370 light-years from Earth, scientists studying with the James Webb Space Telescope have found water vapor hanging about at exactly the same distance from the system star as Earth sits from the Sun.

The discovery is being heralded as an important milestone in the understanding of how rocket planets come to contain water; perhaps the water is there in space while the planet is being formed, such as in the case of this star, PDS 70.

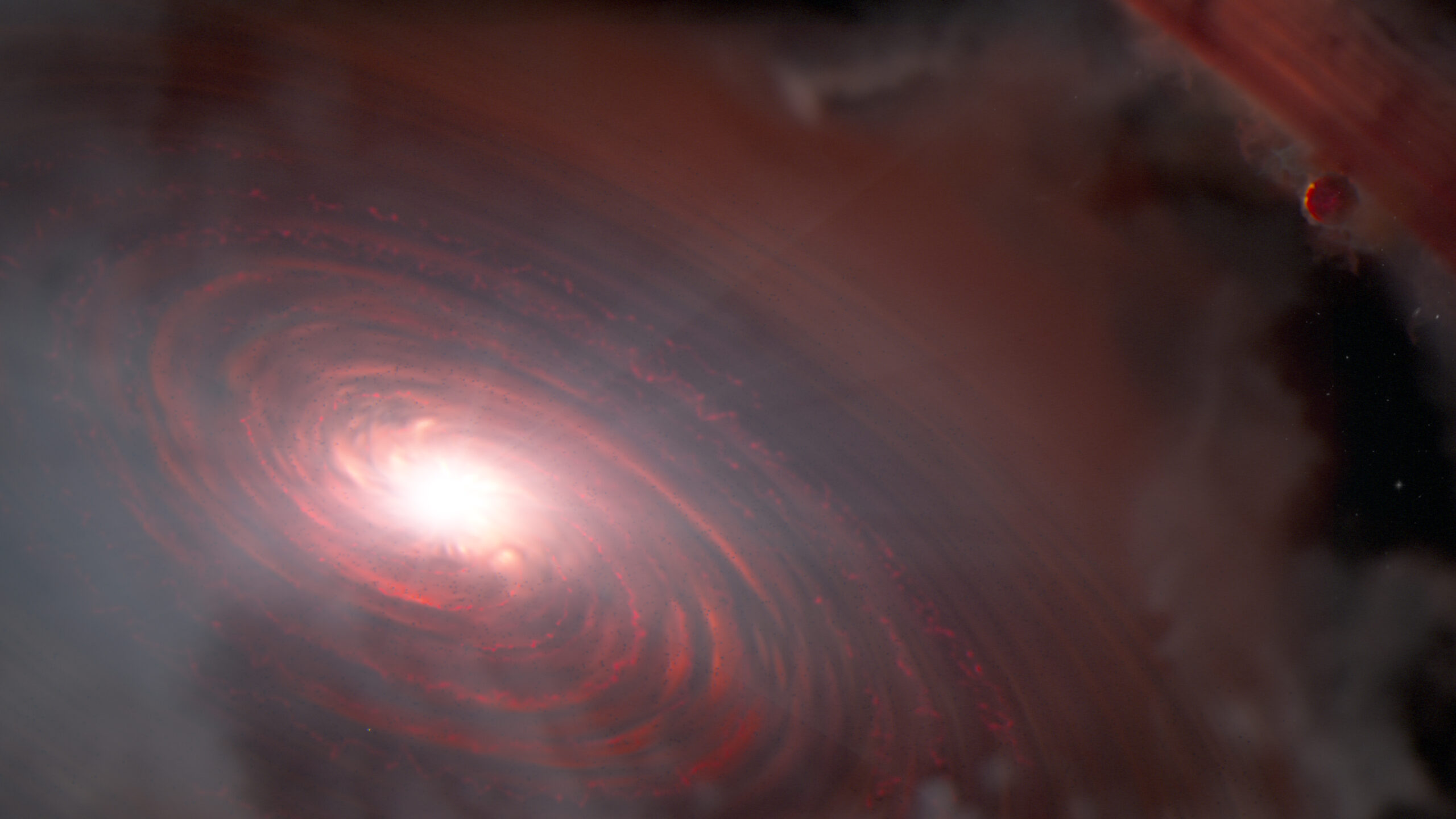

A K7-type star in the constellation Centaurus, PDS 70 boasts two large, dusty ‘accretion disks,’ a term that refers to the rings of gas and dust around young stars that will either be slowly expelled into space or will coalesce into planets. The space between these two disks is 5 billion miles, or very near the distance between Earth and Pluto.

This vast in-between contains two still-forming, Jupiter-like planets: PDS 70 b and PDS 70 c, but the major discovery was the presence of water vapor at 94 million miles from the star, almost exactly the distance from which Earth sits from the sun. Sometimes called the “Goldilocks Zone” for being not too hot and not too cold, it’s also the area that has the greatest chance known to scientists thus far of having a rocky, terrestrial world capable of supporting liquid water.

This is the first detection of water in the terrestrial region of a disk already known to host two or more protoplanets.

Earth is riddled with H2O, and it’s also dispersed throughout other rocky and icy worlds in the solar system, such as Mars. How it got there is still up for debate. Common considerations are that frozen water arrived on Earth and other bodies onboard comets or much larger objects called planetesimals which we know collided as often as perhaps once every day in the earliest period of Earth’s history as an already-formed rocky planet.

Saving it for later

This new discovery, made possible thanks to the MIRI, or Mid-Infrared Instrument, onboard the James Webb Space Telescope, unveils a third theory—that water was available as a floating reservoir in space that formed concurrently with Earth and other planets.

“We’ve seen water in other disks, but not so close in and in a system where planets are currently assembling. We couldn’t make this type of measurement before Webb,” said lead author Giulia Perotti of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany.

Two riddles remain unsolved however. The first is how the water got there in the first place, and the second is how has it survived so long.

The water could literally be forming spontaneously, as hydrogen and oxygen atoms combine in situ, or frozen dust found its way on a course towards the inner disk where gradually it separated from the dust particles.

PDS 70 is a K-type star that’s about 5.4 million years old—very young for a star, but long in the tooth for one which maintains its accretion disks. At just less than 100 million miles from the star, ultraviolet radiation and radiated heat would create temperatures and conditions hostile to the water vapor—potentially 300°C at any time, while the UV would normally be breaking the bonds of the water molecules. The team, which included astronomers at Radboud University, The Netherlands, offered up a hypothesis that the dust in the inner accretion disk could be thick enough to shield the water from the worst of the star’s rays.

Several components, most notably silicates, were detected in the inter-disk media, suggesting that a rocky planet could form there, and if it did, it would have a ready supply of water floating around to benefit from.

The team will continue to use the JWST to survey PDS 70 and hope to learn more about the strange star system. WaL

PICTURED ABOVE: Artist’s concept portrays the star PDS 70 and its inner protoplanetary disk. PC: NASA, ESA, CSA, J. Olmsted (STScI)