It’s difficult to look at the joint statement released by Saudi Arabia and Iran that the old enemies will restore diplomatic ties in efforts to increase regional understanding and solidify their regimes against “common enemies,” and see anything other than the decline of Western influence on the Persian Gulf shores.

It’s also extremely difficult not to notice that the restoration of formal ties was brokered by China, months after they agreed with Iraq to trade oil in Chinese RMB, and a year after they agreed to the same arrangement with the Saudis.

It represents the worst nightmare for the original neo-conservatives that guided the Bush Jr. administration—a power from the East acting as regional guarantor for the largest oil producers on the planet.

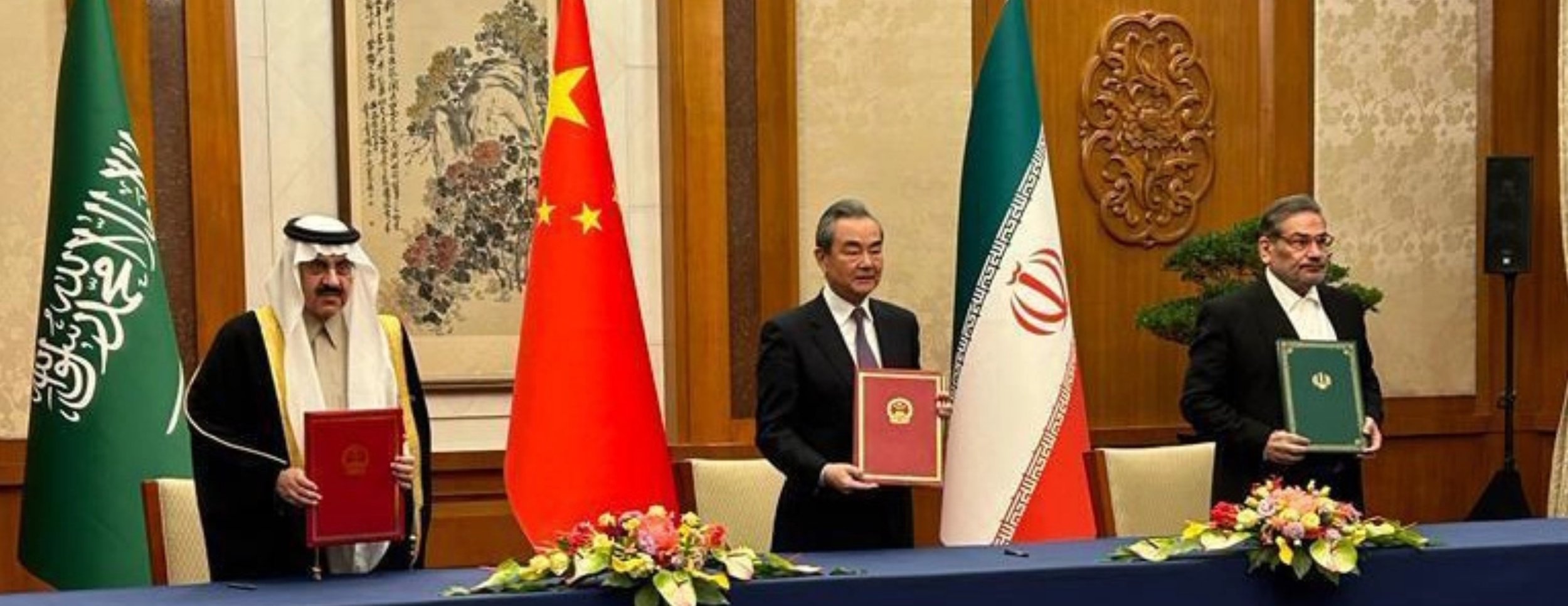

The trend continued the day after the national security advisors of the two Gulf countries made the announcement alongside Chinese Rep. Wang Yi, with an Iranian parliamentary delegation traveling to Bahrain, which also cut ties with Iran in 2016 in solidarity with Saudi Arabia.

The two sides discussed ways of cooperation and coordination in international parliamentary forums, which included the UAE as a sideliner—a development also welcomed by Iran.

“The Islamic Republic of Iran always has a positive approach in cooperation with regional countries and welcomes the UAE’s proposal to expand the level of parliamentary relations and exchange delegations,” said Iranian lawmaker Mojtaba Rezakhah, who led the delegation. “The unity between the nations of the two countries should be more than in the past so that the common enemies do not exploit”.

Old enemies, new problems

In as brief a history as possible, President Jimmy Carter, in a move that garnered the designation “the Carter Doctrine,” agreed to protect the Arabian states like Bahrain, UAE, and Saudi Arabia, from Soviet control or influence in exchange for a promise that the trade of oil from the peninsula would from then on require the US dollar—creating what the neo-conservatives mentioned earlier described as part of the “unipolar moment,” when after the fall of the Soviets the US could remake any part of the world in the image of a Western Democracy.

The theocratic schism between Iran and Saudi Arabia placed them as historic adversaries, yet Iran’s power is ultimately greater than Saudi Arabia’s, so the House of Saud used the US as often as possible to damage and impede their rivals in regional control, oil production, and matters of faith.

Ever since Saudi Arabia launched the war in Yemen however, her relationship with the US has deteriorated. The US did as much and sold as many bombs as it could to support the war effort, without making its involvement front page news as it turned from “Operation Decisive Storm,” the original name for the attack on the Houthi faction that controls Yemen, into a now-8-year genocide with the Saudis unable to accomplish a single strategic goal while hundreds of thousands of Yemeni civilians have died of hunger and disease.

With minimal backing from the Iranian regime, the Houthis, themselves Zaydi Shi’ites, were able to stifle the Saudi attempts to overthrow them at every turn, and even launch attacks on Saudi oil facilities. Securing Iranian support to now end the war as soon as possible will free up public money and other resources for a myriad of other actions.

Iran on the other hand will see China’s entry into the region as a key opportunity to recover economically after European nations like the UK reneged on their part of the JCPOA to protect the Iranian economy from American sanctions.

“Iran considers itself a global player, not just a regional one,” wrote Andrew Parasilti, President of Al-Monitor, in the aftermath of the deal. “It straddles Asia as well as the Middle East. In its score, its peers are as much or more Russia and China, than the Arab states. Saudi Arabia is not considered a major threat by Iran, except as a partner and proxy for Washington. With the deal, Iran wants to take the Saudi piece off the chess table”.

“A lose, lose, lose”

For China, which is the largest buyer of Saudi oil, the accord was struck in Beijing three months after President Xi Jinping, who was recently awarded a third five-year term, visited Riyadh for OPEC meetings.

China’s most senior foreign policy official, Wang Yi, celebrated the signing as a “victory”. “This is a victory for the dialogue, a victory for peace, and is major positive news for the world which is currently so turbulent and restive, and it sends a clear signal,” he said.

Mohammed Khalid Alyahya, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute told the New York Times “that [it’s] a reflection of China’s growing strategic clout in the region—the fact that it has a lot of leverage over the Iranians, the fact it has very deep and important economic relations with the Saudis”.

Undoubtedly, as mentioned at the opening of this article, the worst has come for the Americans, best summarized by Mark Dubowitz, the chief executive of the hawkish think tank Foundation for Defense of Democracies, who called the deal “a lose, lose, lose for American interests”.

By contrast, Daniel Larison, writing at Responsible Statecraft shows what can be accomplished by “not taking sides”.

“U.S.-Iranian ties have been nonexistent for almost half a century. The lack of normal U.S.-Iranian relations has been a disadvantage for the U.S. in all its regional dealings. Washington’s excessively close ties to one bloc of regional states mean that it will never be seen as a credible mediator in any of the region’s disputes,” writes Larison.

“If the U.S. wants to be in a position where it can be a trusted mediator, it has to move away from its one-sided embrace of its Middle Eastern clients and it should seek to cultivate better relations with their rivals. To that end, the U.S. should rule out providing any security guarantees to its clients, and it should not be further fueling a regional arms race with more weapons sales”. WaL

If you think the stories you’ve just read were worth a few dollars, consider donating here to our modest $500-a-year administration costs.