Broad-spectrum antibiotics are widely used in society to treat a variety of dangerous infections, but could they also be driving the obesity epidemic? Several studies, including one published this week in Current Biology have found supporting evidence for this hypothesis.

The study confirmed that the presence of a vibrant gut microbiota—the collection of microorganisms that live inside our digestive tract, gut, and colon, suppresses the drive to consume hyper-palatable foods, and that the disruption of the gut microbiota, in this case through antibiotics, breaks this control and leads mice to over-consume sweetened sucrose pellets.

The gut microbiota is attributable to vast biological catalogs of influence and action, from the immune system (the largest producer of immune cells is the gut microbiota) to our mood.

Today broad-spectrum antibiotics are used for most potentially damaging infections, whether it’s an eye infection, a serious cough, or a urinary tract infection. These medicines however are exactly what they sound like: “anti” meaning against, and “biotic” meaning lifeform. In short, they don’t stop at harmful bacteria but target all indiscriminately.

In the new study, mice had their gut microbiomes disrupted with antibiotics, and several tests were undertaken to measure changes in feeding behavior, circulating feeding hormone levels, glycemia, levels of short-chain fatty acids, and most importantly the changes in the consumption of hyper-palatable foods.

Mice tend to eat in fast, small bouts. The mice given antibiotics that resulted in a total disruption of their gut microbiota not only initiated more of these small feeding bouts of high-sucrose pellets, but the bouts lasted for longer. All 17 of the disrupted mice consumed 50 or more pellets during a feeding session, compared to just 2 of the 16 non-treated mice.

Critically for the study’s hypothesis, previous research has shown that germ-free mice and mice whose gut bacterial communities have been depleted with antibiotics consume greater amounts of a sucrose solution over a 2-day period, but only when the sucrose levels in the solution are high, and not when they’re low,

This same approach was used to see if the mice would also over-consume a high-fat chow diet, which they did, demonstrating the potential for palatability in conjunction with a dysregulated microbiome to drive the over-consumption seen in the new study.

Implications for humanity

One of the many important functions of the bacteria that live in our gut is the metabolization of indigestible carbohydrates (fiber) into short-chain fatty acids like butyrate and beta-hydroxybutyrate.

There have been some studies that show that microbiota containing high levels of butyrate-producing microbes are protective against type-2 diabetes, and indeed, administration of short-chain fatty acids like butyrate has appetite-suppressing effects in mice.

The reason for this is disputed. Some scientists believe that these short-chain fatty acids are an energy source that would be utilized if available. Without it, more energy is derived from simple sugars or other fats which can lead to hyperglycemia, pre-diabetes syndrome, and eventually the real thing.

In the study, restoration of the gut microbiota to a diverse state through fecal matter transplant was enough to diminish the glutinous feeding bouts observed in the dysregulated mice, even when it came from obese mice.

This was also found with the introduction of Lactobacilis johnsonii and gasseri as well as a family called S24-7, a largely uncultured taxon within the order Bacteroidales that’s unlikely to appear in your fermented yogurt or kimchi.

Central regulators of palatable food intake, including dopamine, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and endocannabinoids, differ in the disrupted mice compared with mice with intact microbiotas. Microbiota-mediated effects on palatable food consumption may be expressed through these universal neural compounds.

It’s been shown that just a single course of antibiotics, never mind the several that most physicians will prescribe to treat an infection, is enough to disrupt the microbiome. For years, the largest danger that reaches the ears of the everyday consumer is that over-dependence on antibiotics can lead to antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

However, it should also be stressed that a variety of physiological disruptions, not least of which the complex controls that govern the satiety of hyper-palatable foods, also follow antibiotic use.

It’s reasonable to conclude that society’s own forms of sucrose pellets—those processed and engineered foods designed to overcome the hormonal and physiological barriers to overconsumption, should be kept out of the house following courses of antibiotics, if at least because foods like frozen pizzas, candy, potato chips, and other junk foods have no nutritional value. WaL

We Humbly Ask For Your Support—Follow the link here to see all the ways, monetary and non-monetary.

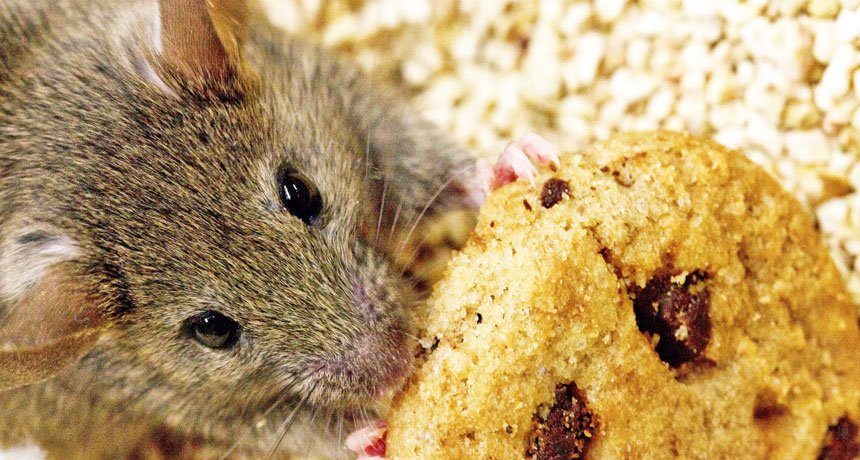

PICTURED ABOVE: Mice begin to feed on sucrose-sweetened pellets in much higher amounts when their gut microbiomes have been disrupted by antibiotics.

If you think the stories you’ve just read were worth a few dollars, consider donating here to our modest $500-a-year administration costs.