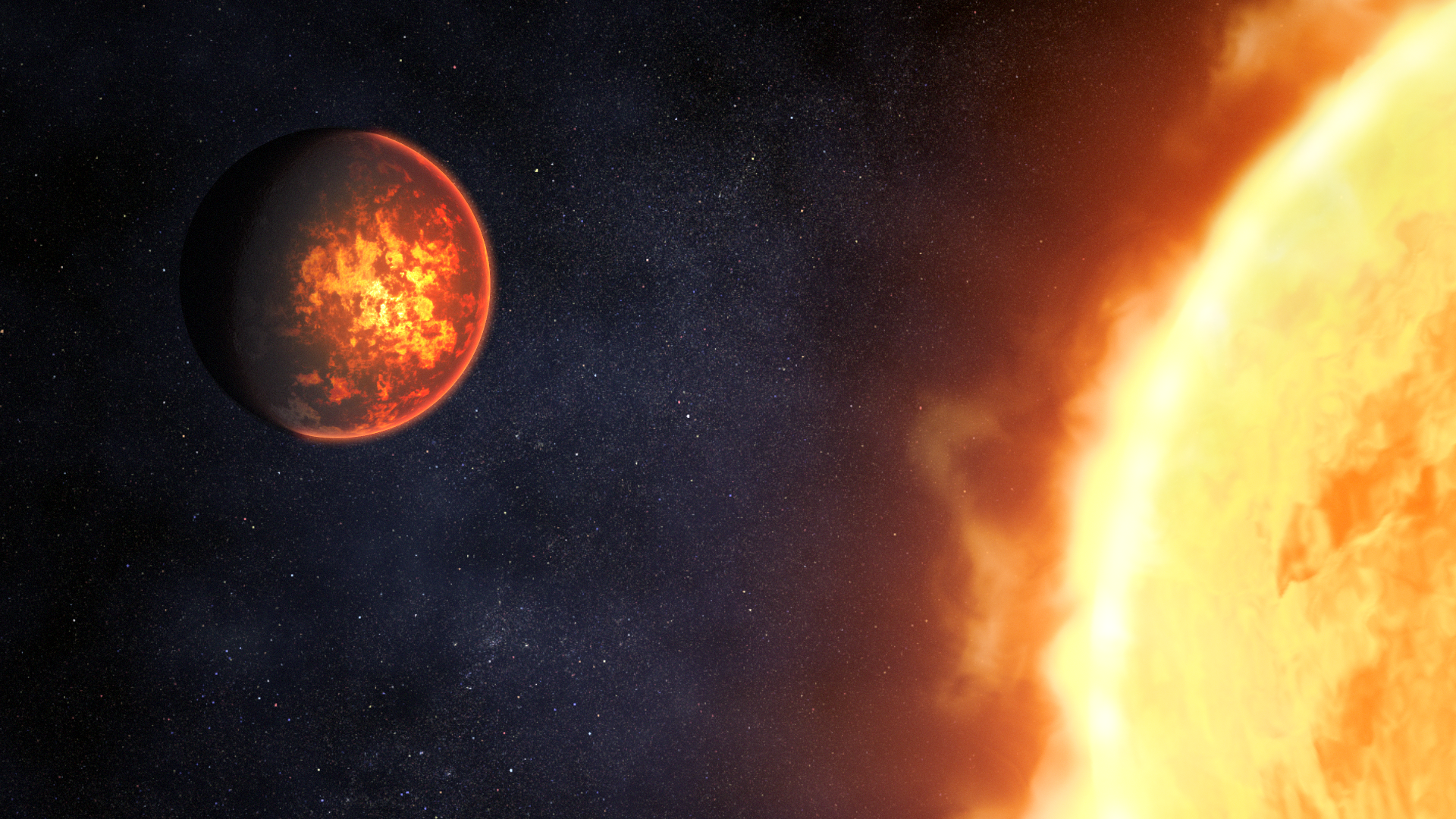

PICTURED: Illustration showing what exoplanet 55 Cancri e could look like, based on current understanding of the planet. PC: ILLUSTRATION: NASA, ESA, CSA, Dani Player (STScI).

As the day of complete alignment and calibration nears for Earth’s most powerful space-based observatory, the operators of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have set their sights metaphorically on a pair of rocky exoplanets in hopes of understanding the geologic diversity of planets across the galaxy, and the evolution of planets like Earth.

They are the lava-covered “55 Cancri e” and the airless “LHS 3844 b”. The former could reveal things about how a dense atmosphere can survive temperatures so hot that moisture condensing in the atmosphere comes down again as lava instead of water, while the latter offers a better glimpse at exactly what kinds of rock are found on rocky worlds.

Both 55 Cancri e and LHS 3844 b are known as “super-Earths” which refers to a kind of rocky world as big as Earth to about as big as Neptune. Exoplanet science has shown that of the just over 5,000 worlds confirmed to exist around stars by science, about 31%, or the second-largest criteria, are super-Earths.

“30 years ago if you said that super-Earth systems would be very, very common among exoplanets in the exoplanets world, you’d probably be called out of your mind,” Dr. Alexander Wolszczan, 75, who discovered the very first exoplanet, told WaL. “It was like a preview of what would happen in terms of the kind of planetary systems we would find later on”.

55 Cancri e orbits less than 1.5 million miles from its Sun-like star (one twenty-fifth of the distance between Mercury and the Sun), completing one circuit in less than 18 hours. With surface temperatures far above the melting point of typical rock-forming minerals, the day side of the planet is thought to be covered in oceans of lava.

On the contrary LHS 3844 b orbits a star that is relatively small and cool, and so the planet is not hot enough for the surface to be molten. Additionally, observations from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope indicate that the planet is very unlikely to have a substantial atmosphere.

These two worlds should be able to tell us a lot about rocky worlds in our galaxy.

PICTURED: The more than 5,000 exoplanets confirmed in our galaxy so far include a variety of types – some that are similar to planets in our solar system, others vastly different. Among these are a mysterious variety known as “super-Earths” because they are larger than our world and possibly rocky. PC: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Raining lava

As 55 Cancri e orbits so close to its host star, it’s assumed to be tidally locked due to the force of gravity. In this case, one side would be permanently facing the searing heat of the star, with the other side in eternal darkness. However brief observations about this world show that the point most directly facing the sun isn’t always the hottest part, prompting curiosity about the possibility of an extremely dense, dynamic atmosphere shifting the heat around.

“If it has an atmosphere, [Webb] has the sensitivity and wavelength range to detect it and determine what it is made of,” said Renyu Hu of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory which will manage the JWST.

JWST is equipped with a spectrograph, which allows the determination of individually-imaged molecules by examination of the color they produce, and near and mid-infrared imaging cameras, which are excellent at producing high-wavelength images of hot or cold objects.

“The infrared is a really good wavelength of light to look at these objects in because a lot of the types of molecules that we expect to see in the atmospheres of these exoplanets have their main signatures in the infrared,” explains Sarah Kendrew, one of the JWST instrument engineers, who told WaL she plans to use her own allocated time to study exoplanets.

With the detection of those molecules, the search for signs of life will be made much easier, as detection of the signatures of basic building blocks can be made much more quickly.

PICTURED: Illustration comparing rocky exoplanets LHS 3844 b and 55 Cancri e to Earth and Neptune. Both 55 Cancri e and LHS 3844 b are between Earth and Neptune in terms of size and mass, but they are more similar to Earth in terms of composition. PC: ILLUSTRATION: NASA, ESA, CSA, Dani Player (STScI).

These instruments will allow Webb to see where heat is dispersed on 55 Cancri e, and whether or not it’s an atmosphere doing the dispersing.

Another intriguing possibility, however, is that 55 Cancri e is not tidally locked. Instead, it may be like Mercury, rotating three times for every two orbits (what’s known as a 3:2 resonance). As a result, the planet would have a day-night cycle.

In this scenario, the surface would heat up, melt, and even vaporize during the day, forming a very thin atmosphere that Webb could detect. In the evening, the vapor would cool and condense to form droplets of lava that would rain back to the surface, turning solid again as night falls.

Airless and cold

Contrary to lava-raining Cancri e, LHS 3844 b is airless and colder. Here too, JWST’s spectrograph can reveal exactly what materials the planet — in this case the rock and not the atmosphere — is made from.

“It turns out that different types of rock have different spectra,” Laura Kreidberg at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, explained to the JWST press team. “You can see with your eyes that granite is lighter in color than basalt. There are similar differences in the infrared light that rocks give off”.

Kreidberg’s team will use MIRI to capture the thermal emission spectrum of the day side of LHS 3844 b, and then compare it to spectra of known rocks, like basalt and granite, to determine its composition. If the planet is volcanically active, the spectrum could also reveal the presence of trace amounts of volcanic gases.

These are just two projects that will be conducted over the first year of observations with JWST. At the moment there have been 6,000 hours worth of dozens of projects already awarded.