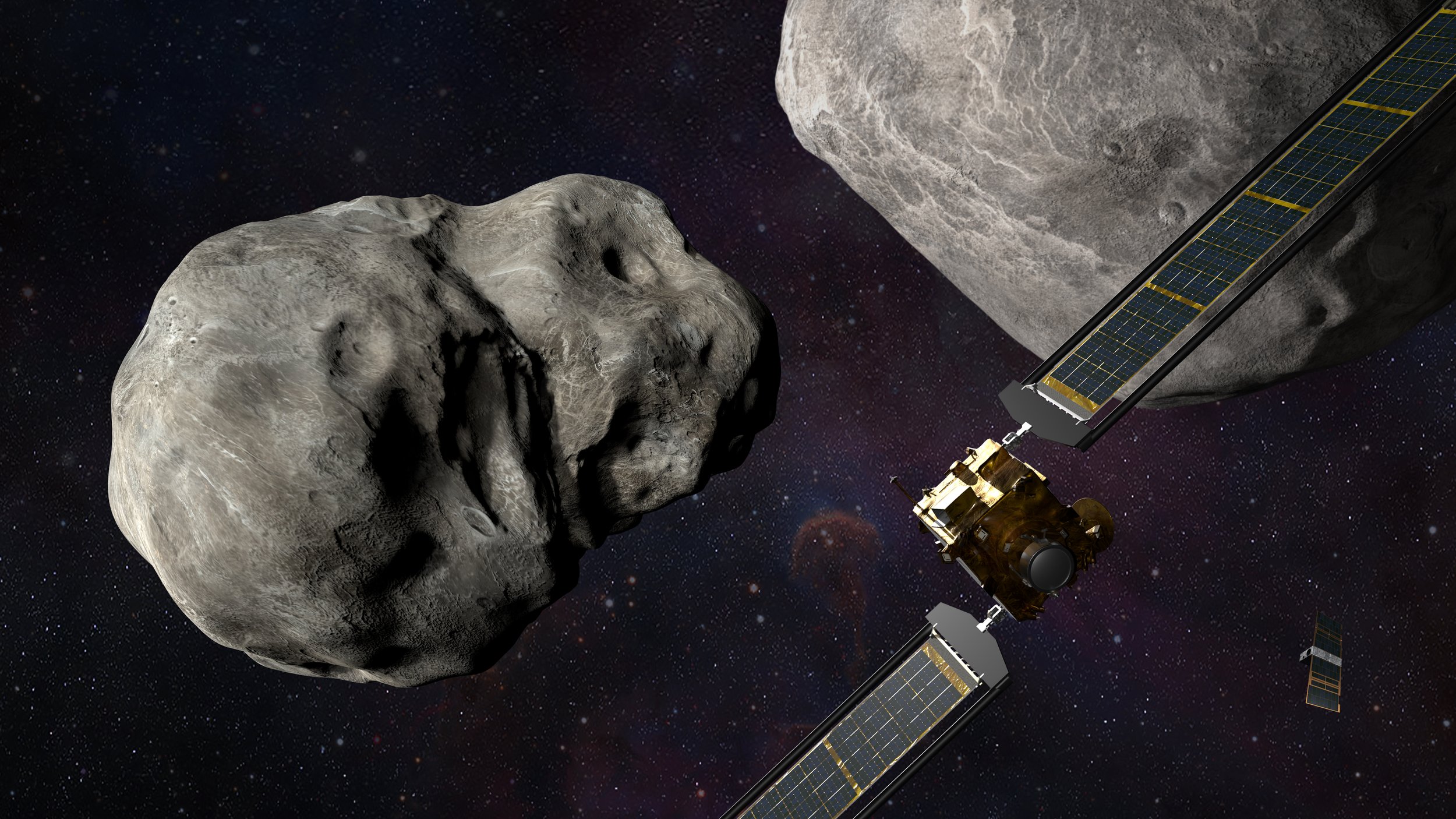

PICTURED: Illustration of the DART spacecraft flying into the asteroid Dimorphos. PC: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben.

Can slamming an object into an asteroid many times its size be enough to save the Earth from a catastrophic event? A new mission from NASA, slated for imminent launch will seek to answer this question when in about 10 months, the DART spacecraft hurtles into an asteroid.

For years scientists have urged more money and research be invested into the capability to deflect incoming comets and asteroids, an area of study known as planetary defense, and DART is the first-ever to test asteroid deflection through a kinetic impact.

The target for the demonstration is a harmless asteroid called Didymos, which has a satellite asteroid about one-fifth its size orbiting it every 11 hours or so called Dimorphos. DART, or “Double Asteroid Redirection Test,” will slam into Dimorphos head on, attempting to alter the orbit of the larger Didymos as a result of gravity by a small degree.

Neither asteroid will ever be in the path of Earth, and while no asteroids on an Earth-threatening path have been identified, it’s well-known our planet has been hit in the past.

For starters there is the asteroid which impacted the Yucatan 66 million years ago and took out the dinosaurs. In our epoch, the Tunguska meteor airburst in 1908 which exploded above remote Siberia with a force of 12 megatons, leveling 80 million trees across 830 square miles, and the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor explosion which injured 1,500 people and damaged over 7,000 structures after it burnt up in the atmosphere with a force of 26 Hiroshima bombs, have elevated the concept of planetary defense to something worth investing millions in.

DART is the first mission resulting from those millions, and is the first-ever from the recently established Planetary Defense Coordination Office at NASA.

DART will launch on November the 24th, at 1:21AM EST, when it leaves from the Vandenberg Air Force Base aboard a SpaceX Falcon9 rocket. Pre-launch coverage to begin on NASA’s YouTube channel at 12:30AM.

A well-studied explosion

“Our number one technology is SmartNav,” said Nancy Chabot, DART coordination lead, on a recent radio interview with the Planetary Society. “The asteroid is only 160 meters in diameter, less than two football fields… There are these two asteroids, and you can’t actually… tell the difference between images of Didymos and Dimorphos until the last hour of the mission”.

The last hour, referring to the hour before impact, will see a very powerful camera take pictures of the two asteroids. The images, interpreted by the algorithms of the SmartNav system, will be used to calculate the exact thruster fire of the spacecraft to ensure it impacts into Dimorphos and not the larger Didymos.

“One of the other challenges with this is we don’t know exactly what Dimorphos looks like; we’ve never seen it before and we know asteroids have all kinds of weird shapes,” said Chabot. “So we’ve been doing extensive testing using all different asteroid shapes”.

DART will be carrying a small cube satellite, designed by the Italian Space Agency, along its course to impact with Dimorphos, releasing it about 10 days in advance of the collision in order to record the data of the explosion. It will make a flyby of Dimorphos about 3 minutes after impact to take images of the debris broken away from the asteroid, as well as detailed pictures of the asteroids themselves.

The well-studied explosion will inform future missions and push along the science of asteroid composition, but the most important finding will be whether or not you can run a spacecraft into an asteroid or asteroid system and blow it off a potentially disastrous collision course with the Earth.

It seems a lot of time, money, and effort to build a vessel for the sole purpose of destroying it, but compared to research and development budgets for weapons manufacturers to fight wars more effectively against our fellow man, a few million to know whether we could save ourselves from a meteoric apocalypse seems well worth the pennies.