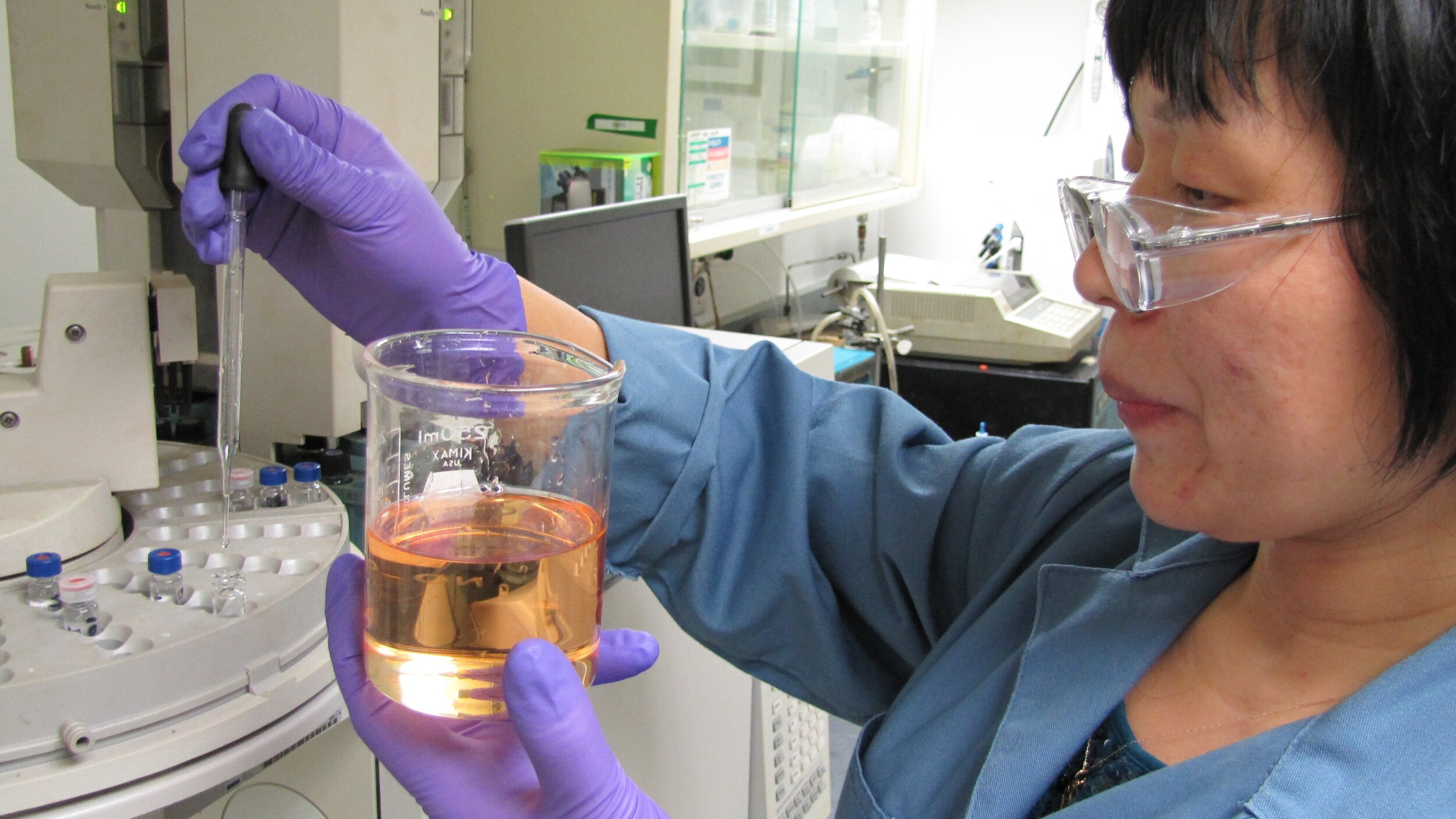

PICTURED: An Aerojet Rocketdyne researcher examines a container of the Advanced Spacecraft Energetic Non-Toxic (ASCENT) monopropellant during preparation for flight testing. Photo credit: Aerojet, retrieved from NASA.

A recently completed mission from NASA has demonstrated the effectiveness of a new state-of-the-art “green” rocket propellant.

The mission, designated Green Propellant in Space (GPIM), saw a small satellite fly up into orbit on a Falcon Heavy rocket 16 months ago, and demonstrate the capability of the non-toxic fuel to power small spacecraft.

First developed by the Germans to power the Messerschmidt rocket-powered jet fighter in World War II, hydrazine is the currently-utilized monopropellant for craft operating in the vacuum of space, and has powered missions like Viking, and the Curiosity Rover.

However hydrazine is very toxic, and presents a serious health hazard to anyone whose job it is to handle it. Seeking to address these concerns, the Air Force Research Laboratory at Edwards Air Force Base, California, developed a low-toxicity alternative that they hoped would also solve some handling issues.

“If I were to try and make an industrial/household chemical comparison I would liken hydrazine to a more toxic version of ammonia and ASCENT (the green propellant) to liquid fertilizer,” Adam Brand, advanced propellant development lead at AFRL, told World at Large.

At first, engineers weren’t sure how the new fuel, called “AF-M315E,” would work with existing craft. Space News reports that AF-M315E, thankfully renamed “ASCENT”, created a lot of water as a byproduct. Therefore the GPIM craft was equipped with all-new thrusters and associated equipment, making the 2019 test flight a big deal.

However the mission was a complete success, demonstrating that not only is ASCENT far-less toxic than hydrazine, but produces 50% more fuel economy compared to its predecessor as the GPIM test craft met it’s stretch goal of 10,000 individual thrusts.

PICTURED: The GPIM spacecraft floats over the Earth in an artist’s rendering.

Green in a difference sense

Obviously CO2 emissions aren’t a concern hundreds of miles above the atmosphere. And since it isn’t made for ascent rockets like a Falcon 9 for example, ASCENT is green in the sense that it’s far-less toxic and easier to dispose of than hydrazine.

“ASCENT is a salt solution and therefore has a negligible vapor toxicity so it can be handled with standard personal protective equipment such as gloves, goggles, and a labcoat,” says Brand.

“Conversely, for hydrazine which is a volatile suspected carcinogen, personnel must don Self Contained Atmospheric Protective Ensemble suits. The loading and disposal of hydrazine is a costly and time consuming operation,” he added.

Spacecraft, like so many other things these days, are getting smaller. Micro satellites, are becoming very popular forms of research equipment, and ASCENT is ideal for these sort of craft.

“The high energy-density of this monopropellant makes it particularly beneficial for volume limited spacecraft,” says Brand. “I don’t think that ASCENT completely replaces hydrazine, I would like to see a suite of in-space propellants from which to choose for a particular mission”.

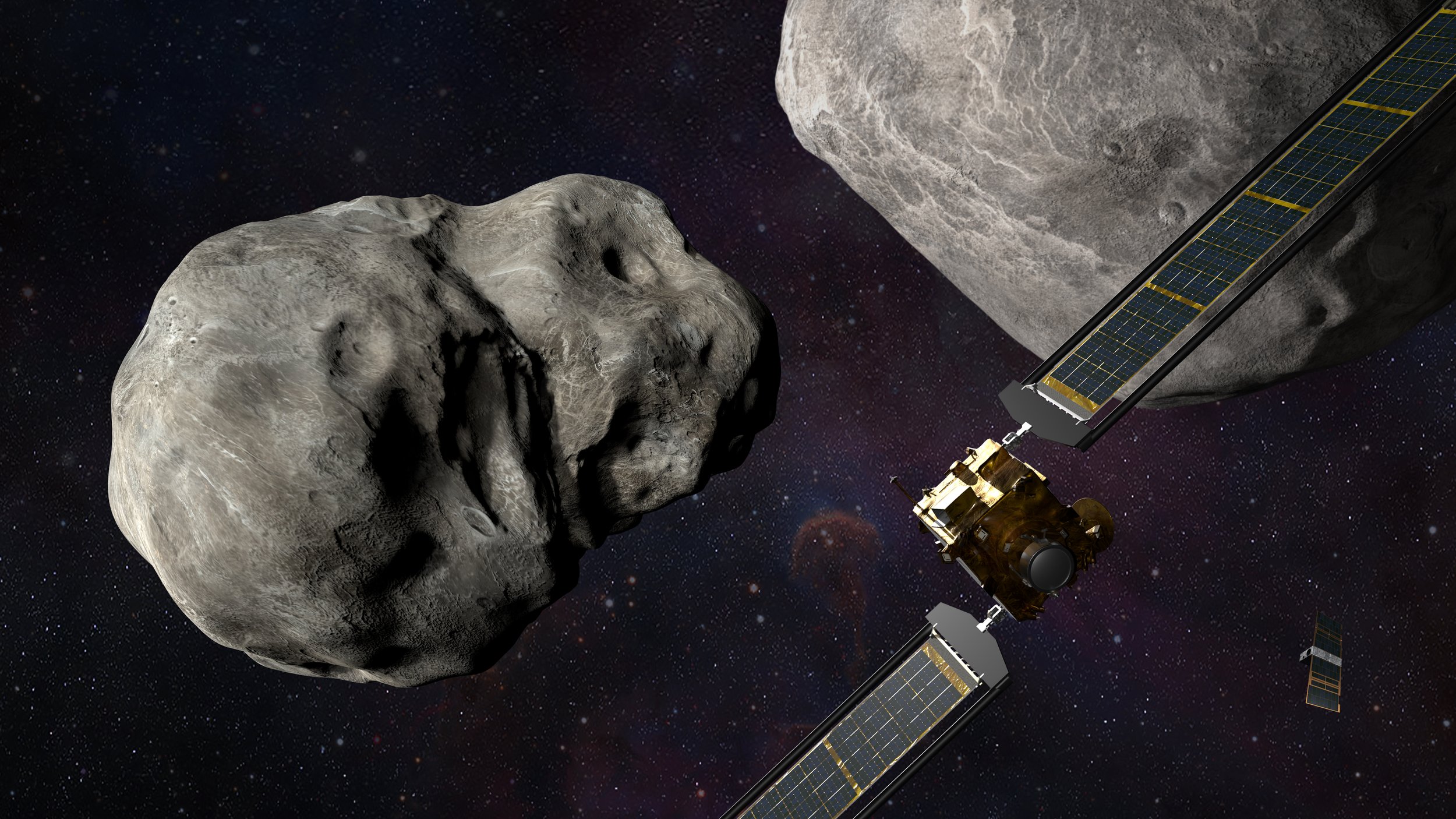

The next one of these small spacecraft to be deployed with ASCENT will be the NASA project Lunar Flashlight, set to join as cargo with the Artemis I mission to the moon on the inaugural voyage of the long-awaited Space Launch System of massive NASA-built rockets.

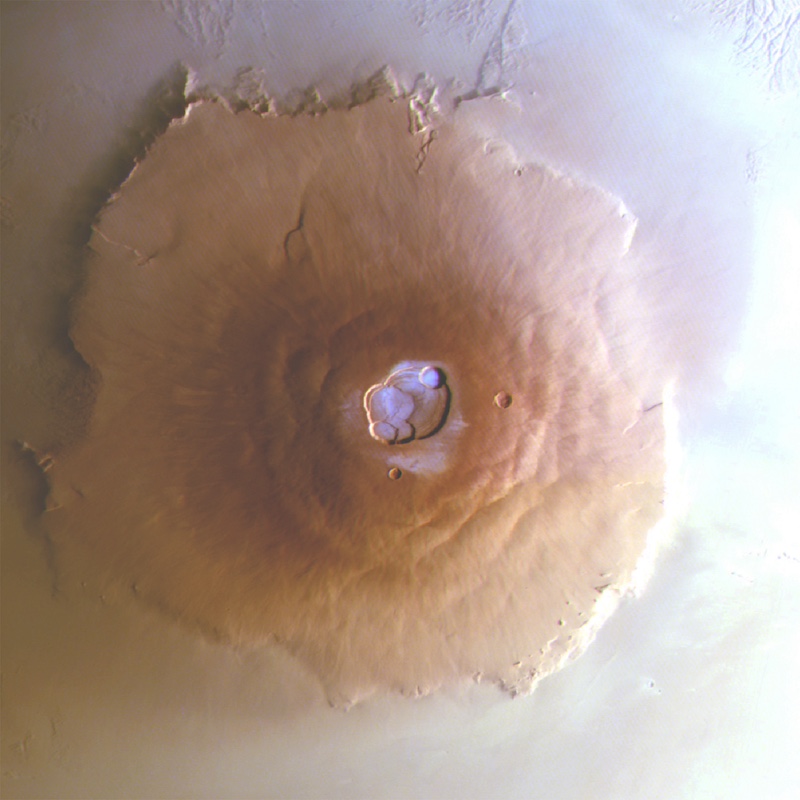

Roughly the size of a briefcase, Lunar Flashlight is a very small satellite being developed and managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the same group of boffins that remotely pilot research craft like Curiosity. It will use near-infrared lasers and an onboard spectrometer to map ice in permanently shadowed regions near the Moon’s south pole.

ASCENT will allow Lunar Flashlight to travel farther for longer, while the increased number of thrusts will also allow it to make more precise and complicated maneuvers.

“The ASCENT propellant is… more expensive than hydrazine, but this small cost is in the noise of the cost of a spacecraft,” explains Brand. “It’s like buying a race car for only one short trip and having to pay $6/gallon for gas”.

Looking into the future, ASCENT’s low toxicity means that it would present far fewer challenges to bringing the propellant onboard larger, manned-spacecraft, in order to refuel smaller research craft, and avoid the highest of all costs, the cost of launching things from Earth.