Desertification – a phenomenon that for the longest time was associated with deserts, is actually much more to do with farming. A 1977 paper from Texas University of Technology described it thusly: “…the process of deterioration of plant cover in semi-arid lands,” yet the author’s reference material also included a term called “desert-creep” which more aptly describes the modern misconceptions about desertification, namely desert zones encroaching upon steppe zones, encroaching upon savannah, encroaching upon forests.

Africa’s Great Green Wall project, a remarkable effort across over 10 countries to build a giant patchwork strip of vegetation to combat desertification in Africa’s Sahel region – the band of semi-arid yet arable land south of the great Sahara, swaps the word desertification for land degradation.

While certainly less forebodingly romantic as the idea of a desert that begins to swallow the lands on its border, land degradation mainly stems from unsustainable agriculture and livestock practices. The lands adjacent to deserts just happens to be more susceptible to this effect due to their aridity, and the Sahel more than most, possibly because of the political and economic instability of the region.

Befuddlingly, Africa’s Great Green Wall is only matched in world land degradation initiatives by China’s Green Great Wall.

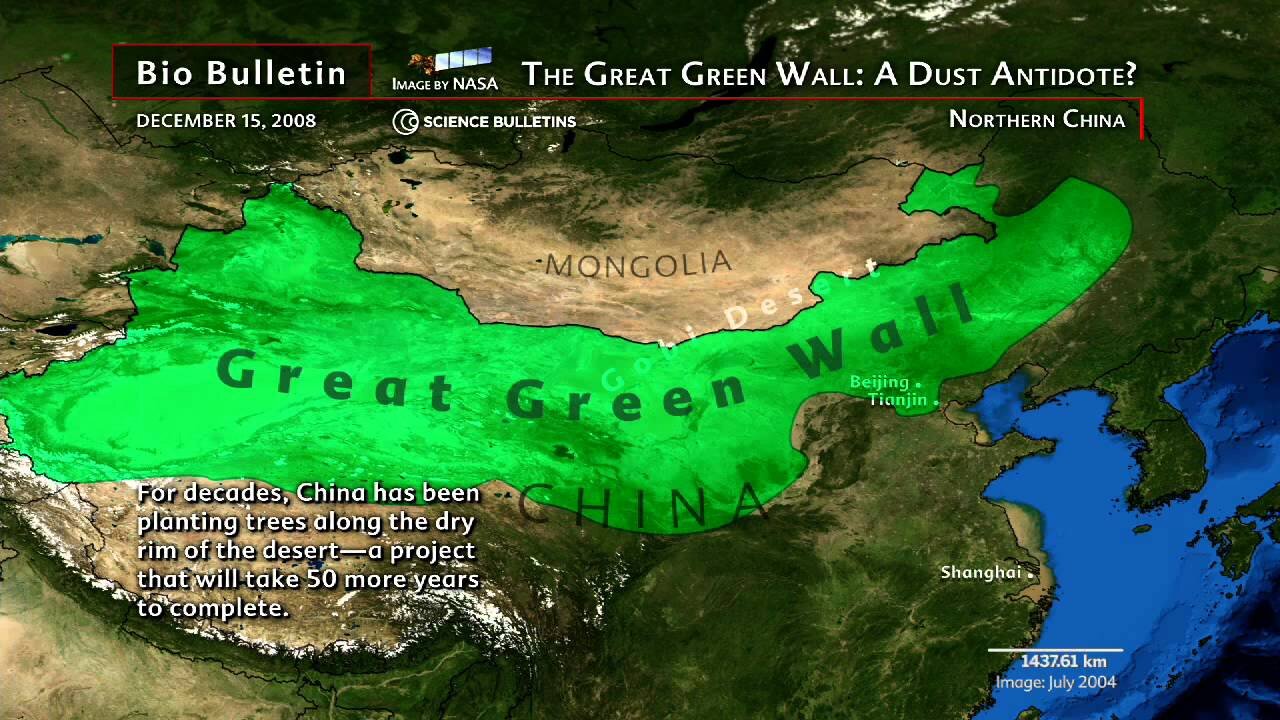

PICTURED: The scope of the Green Wall of China, as it seeks to act as a buffer to dust storms and land degradation. Photo credit: American Musuem of Natural History.

The Green Wall of China

The deserts to the north and west of the Chinese heartland make up one fourth of the country’s landmass. The Gobi of Inner Mongolia, and the Taklamakan, north of Tibet, still represent places where the natural world reigns undisputed.

The Great Wall of China built 2200 years ago in the Qin Dynasty by the 1st emperor of unified China, Qin Shi Huang, was intended to keep out barbarians. This new initiative started in 1978 is meant to be a bulwark against the ever-expanding Gobi. Dubbed the “Green Great Wall” more than 66 billion trees have been planted.

Over the last few decades northern Chinese cities like Beijing and Gansu have gradually become accustomed to dust and sand storms, and so the marches of young trees will follow a 2,800 mile long border on the edge of the Gobi desert in the Chinese region of Inner Mongolia, and stretching to Uhigarstan and the border with Kazakhstan.

According to the United Nations’ Convention to Combat Desertification, more than 24 billion tonnes of fertile soil is annually lost from land degradation, and while the Green Great wall is nearing completion, observations about its efficacy are mixed.

PICTURED: Short midday shadows on the dunes of the Gobi.

In an excerpt from the book The World in a Grain: The story of sand and how it transformed civilization journalist Vince Beiser remarks on the problems with this massive afforestation project.

“Many of the trees, planted in areas where they don’t grow naturally, simply die after a few years. Those that survive can soak up so much precious groundwater that native grasses and shrubs die of thirst, causing more soil degradation. Meanwhile, the government has forced thousands of farmers and herdsmen to leave their lands to make way for the desert-fighting projects”.

In another cutting from his book, Besier quotes Forestry Professor Cao Shixiong” about the politics of mass tree-planting.

“When there’s profit at stake, people tell lies. The central government gives out billions of yuan every year for tree planting. So there are many companies that want to take part. They’re not concerned with the environment, but with profit”.

Besier notes other environmental problems like insects.

“A few years back a pest, a particular kind of beetle, hit one big chunk of the Green Great Wall and wiped out 1 billion trees almost overnight,” he says. Unfortunately, as Prof. Cao points out, the same people who are receiving money for planting trees are the people who produce the data on the success of their operation. Unsurprisingly, reliable data is hard to find on whether or not China’s green wall is any ways “great,” for the ecosystem.

Africa’s Great Green Wall

Taken from an earlier World at Large article:

Africa’s Great Green Wall is a project to plant and grow a forest/agri-ecosystem across the entire width of the continent, spanning 9 thousand kilometers, and crossing through more than ten countries – from Senegal in the west to Djibouti in the east.

In Senegal 12 million drought-resistant trees have since been planted and 4 million hectares of arid land has been restored. A virtual-reality film called Growing a World Wonder documenting the scale and ambition of the project was released in 2015 to resounding success and is available on their website.

It might have grounded to a halt at the borders of Senegal, hugely involved as they are with the Great Green Wall project, but the success has continued – particularly in Niger. A poor developing country that consistently ranks towards the bottom of the United Nations Human Development Index, Niger has benefited tremendously from the Great Green Wall.

5 million acres of shattered land has been restored, reclaimed, and revitalized. Nigerien grain yields have increased by 500,000 tons per year, feeding an additional 2.5 million people. Most of the results have come on the back of traditional and innovative farming techniques as well as natural regeneration strategies to bring life back as it was before into deserted, arid farm land.

“We’ve never seen anything near this size and impact on the environment anywhere in west Africa,” says Gray Tappan, a geographer with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Rather than unfurling like a curtain, work has started sporadically along the Wall’s path. In Ethiopia, 15 million acres of land has been restored, while Burkina Faso and Nigeria have also seen tremendous land-restoration.

A quilt of land-use practices

Unlike China’s frenzied tree planting, Africa’s Great Green Wall is a patchwork quilt of different types of vegetation, and unlike containing the spread of the desert to the north, Africa’s wall is also to bolster the local economy and reclaim land use for a population that is expected to triple from 100 million to 340 million by 2050.

Plans to create resilient local economies that can survive droughts have also gone hand in hand with improving the access to reliable and quality water sources and sewage, saving women and girls hours which they would normally spend gathering water. Projects are involving entire communities, improving income and even education levels for everyone.

With every hectare of revived land, green jobs are created, as well as job training for unemployed citizens.

But organizers and leaders are looking even further, believing that Africa’s Great Wall will take away the hopelessness that leads many young Malian or Mauritanian men to throw their lot it with terrorists.

“When you have no money and no job and the terrorists come and pay, people say yes,” explains Kouloutan Coulibaly, Mali’s Director of Forestry. “It’s an opportunity for them.”

“Terrorists recruit people with money, they make them feel important and when you have nothing you are easily brainwashed,” he says. “The Green Wall is about giving people alternatives.”

Land degradation and climate change

Lost in the chatter and portents of apocalyptic persuasion that pervade the world discussion on climate change are much more obvious forms of general environmental degradation that drive men, women, and children into poverty around the world every day.

Land degradation is an enormous threat for people across the globe, from India, to Mongolia, to Mexico. It’s accentuated by warmer temperatures whether man made or otherwise.

On the bright side these massive planting operations are adding to the very realistic possibility that we can solve the proposed climate change triggering mechanism of carbon entering the atmosphere. Earlier this year, a widely reported study modeled the possibility of avoiding the worst of climate change by planting a trillion new trees.