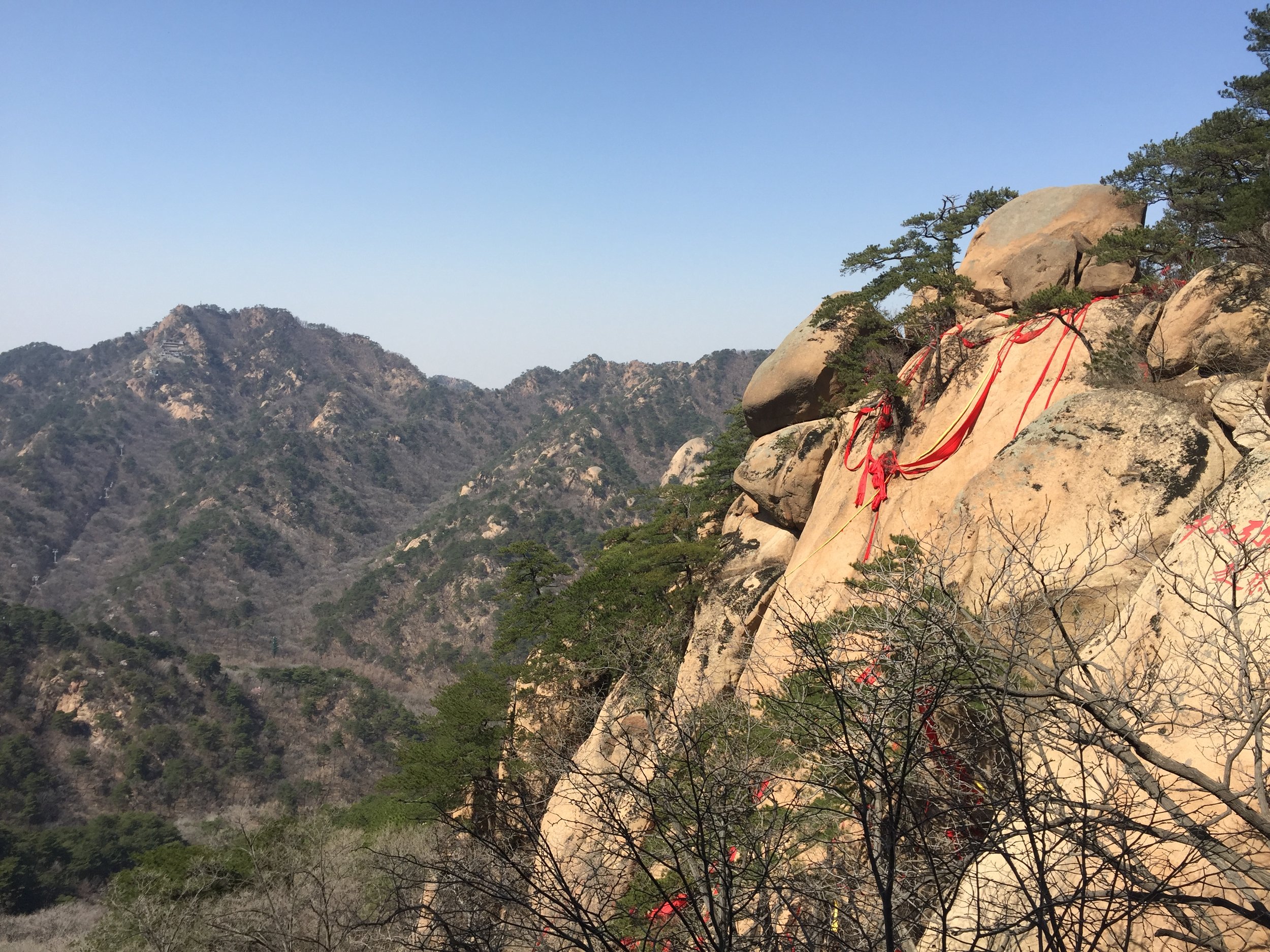

An older, distant China is, as I mentioned earlier, quite hard to find here in the Northeast. But this doesn’t mean there is nothing cool to do or beautiful to see. Last weekend I was fortunate enough to visit Qian Shan National Park, one of 277 national parks and scenic areas in this Middle Kingdom. Qian Shan, like many mountains in China, are actually quite young. The Thousand Lotus Petal Mountains, as they are called, thrust their burnished pinnacles up from the bosom of the earth a mere 4 million years ago. With so little weathering, they retain the pointy karst-rock appearance which so typically captures the spirit of China’s mountainous regions. Now there aren’t many places of any significant elevation in the Northeast of China – Qian Shan being one of the main exceptions. If you folks don’t know, the Q is pronounced like CH, through the shape of a T. Qian Shan is important to this region as a sacred mountain range. Several Taoist masters have supposedly ascended to heaven to become immortals within its sheltered valleys and beetling precipices.

Taoism is a very difficult faith to explain, and if anyone is curious about its aspects or tenants, I can recommend a lecture series by Italian-American history professor Danielle Bolelli which you can search for on google – “The Taoist Lectures.”

Taylor and I took a high speed train from Shenyang to Anshan; roughly a 36 mile journey. The space between these two Rustbelt cities will both haunt and fascinate me as long as I live. The seat was very comfortable, and as I settled in for the quick 30 minute trip, I was very curious as to what the outskirts of the city I have spent 4 months in would look like. Knowing the harsh and cruel realities of the world from my time in Nicaragua and Colombia, I expected the worst. Instead I got something more suited to a dystopian science fiction story like Judge Dredd or Blade Runner. What I saw needs some brief explanation. China has 1.5 billion inhabitants, four times the population of North America – the same numbers as North America and Africa together, so they don’t mess around with civilian housing developments. Whichever bureau handles land permits and zoning doesn’t even get out of bed for less than a 32 story tower, and quite rightly don’t even pick up the phone if you aren’t building at least 4 at once. I expected upon breaking the boundary of the metropolitan heart to see ghettos, and lots of them. Instead I was greeted with a sight otherworldly; bristling neighborhoods of identical skyscrapers stretching off as far as the eye could see, the morning sun low on the horizon trying to peep through the sequoia-like forest of cement, glass, and steel. These patches of communities continually reappeared no matter how far we got from the city until they were literally alone; without cars, people, corner stores, or anything. Just roads, sidewalks, and giant towers stuck in the middle of a ravaged, flat countryside. Beyond these “Ghost cities,” high rise apartments continued along the horizon line in geometrically identical grids, but these ones lacked paint, windows; a concrete jungle yet in the womb, waiting to be born into the strangest environment I’ve ever seen.

Mind you, dear reader, these lined and dotted the distant background from my view out of the window – the foreground was taken up with farmland. The city, an ever-devouring beast, removed the idea of suburbs from the zeitgeist, low stone walls and compacted earth marking the place where an entire town may have stood before being forced to join the modern crush. The barren fields looked hazy and dusty, without any clear sign of irrigation. But I began to see small cone-shaped mounds dot the land in the foreground. It was immediately clear these were graves, as flowers or other trinkets of affection lay upon them. The number of graves began to expand rapidly as we got farther and farther out of Shenyang until the ground was riddled with them; such that it must have been hard to roll a wheelbarrow from one field to another. I remember hearing a story that back in the late 19th century, American’s observed the passing of legislation which deemed any land or property deed designated a historical site, or a graveyard become forever unmolestable; to stay in one’s family for all time, to be free from any land redistribution, and to be unchanged in any capacity. Americans immediately began doing anything they could to get their properties designated a graveyard. It looked as if the Chinese recently had the same moment, as the graves of their family members sat everywhere, and anywhere – roadsides, hilltops, backyards, the middle of cornfields, near the irrigation networks, and in the ruins of old buildings.

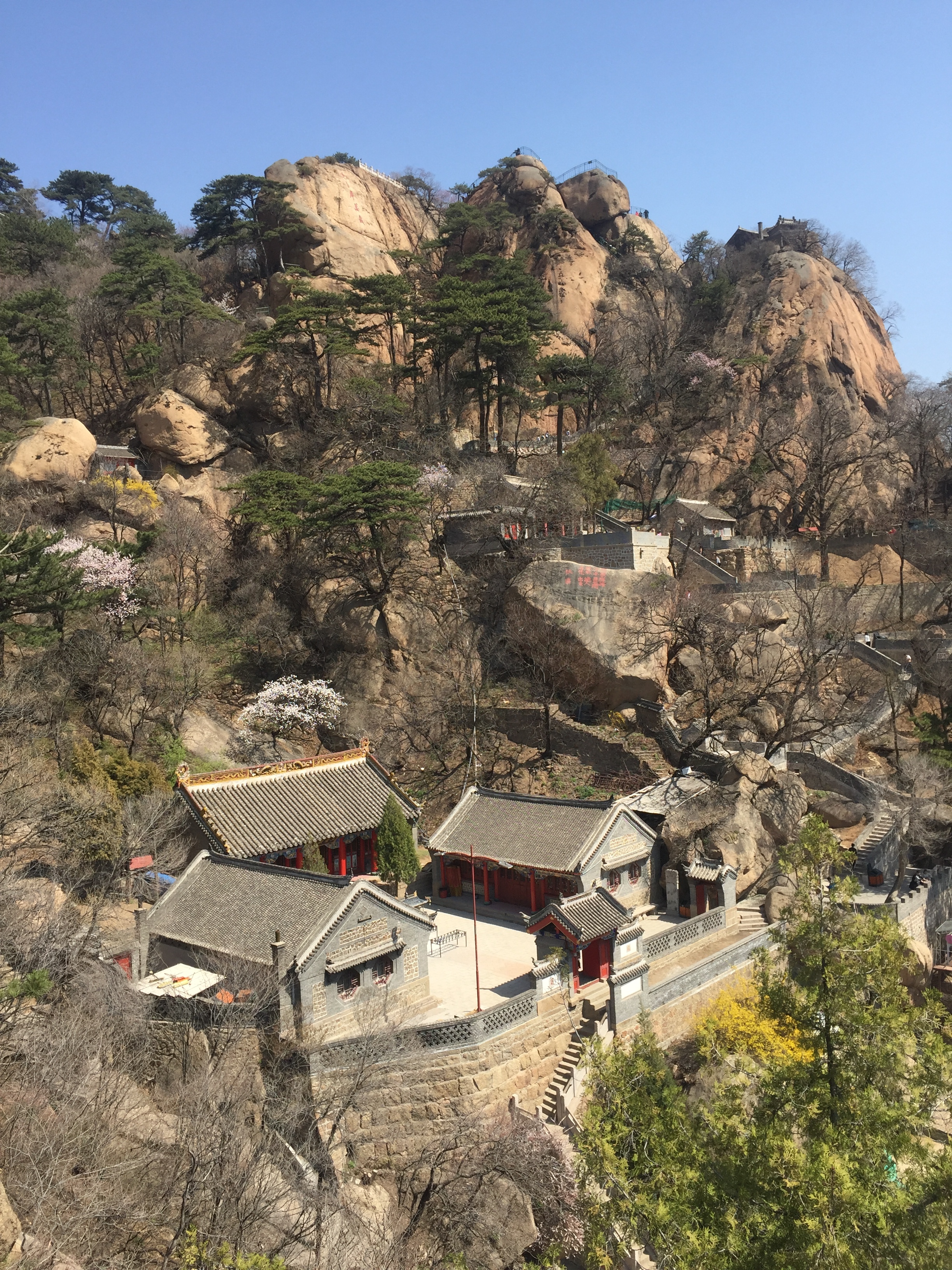

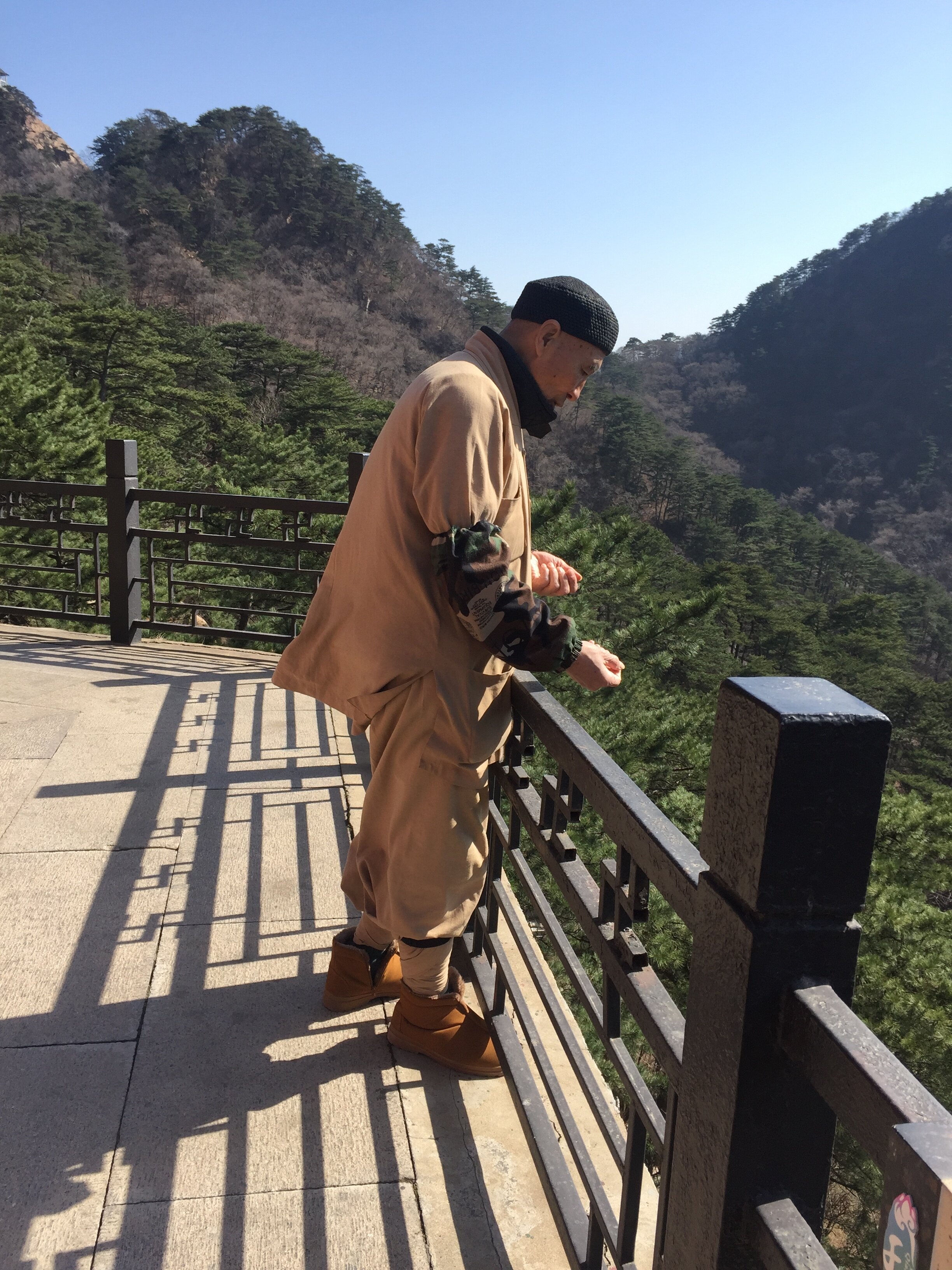

I was sufficiently amazed by the time Taylor and I reached Anshan. Having checked into our hotel, we went straight to the mountains. Anshan is another industrial steel and iron town in the Northeastern rustbelt, but was far greener than Shenyang. It’s also more white and pink, because the cherry and peach blossoms are out! As our taxi took us into the mountains the slopes looked like they were covered in snow or smoke from all the blooming trees. Right away the first thing that hit me was that this was not a national park – it was like watching a documentary while sweating. No one there looked remotely in shape or familiar with their outdoor surroundings (considering Qian Shan was the first area where it seemed nature was truly allowed to simply go about its natural business) and they dressed without any idea of the perils which await clothing in the mountains, or that they were entering the natural realm at all! A larger concentration of people there wore face masks than here in the cities! This distressed me greatly. Dressed in Boy London, faux Gucci or Versace, with large garish sunglasses and surgeon’s masks pulled over their faces they looked like manikin phantoms; distrustful of the clean, pine flavored mountain air. Taylor and I climbed high up to the Taoist temple I mentioned earlier – an entirely vertical stone world. Temples floated almost in the sky on platforms of stone built two-hundred years ago, tucked into the mountain side and vanishing amid the dark grey-green pines and Sugar-in-the-raw colored stone. One might completely mistake the vertical labyrinth of winding stairs, secluded temples, and sheltered switchbacks as just queer features of an overall curious oriental mountainscape. The steps that took us from one sacred pagoda, one incensed-bathed hall, one manicured meditation spot to the next ran steep like Inca stairs in a Peruvian ruin; and they hid like innocent children behind buildings and around sharp corners. It really felt like maze since we came up one way, got lost, before descending back down to the valley by a completely different way. Some tourists had steam enough to brave the large count of staircases; most of them were older folks. There were Taoist monks as well, walking around in midnight blue or grey raiment, strange, white, almost bonnet-like hats, going about their day as they would have done for two hundred years. They paid us no mind, and we did not disturb them.

From the top of the valley we looked across at a beautiful Buddhist monastery. This is one of the central features of the Qian Shan, because normally Buddhists don’t share space with Taoists. Qian Shan is an exception to that rule, and so we hurried down for a visit. Now, it was extremely pleasant and beautiful, but it was built by a modern Buddhist association; so we enjoyed ourselves quickly and moved on.

Farther up the main road into the mountains, Taylor and I turned off into the forest, passed through a campsite, before mounting a flagstone staircase to the left and moving towards the Maitreya Buddhist Scenic Spot – the largest naturally occurring image of Siddhartha Gautama on earth. I had very little knowledge of the area beyond what I could find on Wikitravel, so after probably a hundred steps, I was not to know one hundred steps marked very little actual progress up the staircase. Up we went into the pines, the grey stone of the Water Dragon Temple gleaming in the sunlight behind us on the slopes of the other side of Peach Blossom Valley. Long streamers of prayer flags of green, blue, white, orange, red, and yellow, marking the classical elements of water, wind, fire, wood, earth, and iron if I’m correct, tied up at the temple’s roof cascaded down over the courtyard of the mountain sanctum and could be seen from a hundred miles away. Marking in our minds from the base of the mountain, an image of a golden spike upon the highest foreseeable peak, we knew that was where we wanted to end up, and the ridiculously precarious staircase began to suggest we were getting nearer to our goal. The stone became no wider than our feet, the steps spaced two feet above the last; so steep that the top of every section promised a false horizon. There were no people at all that high above the road, and I felt a little like Golumn, Sam, or Frodo climbing the secret stair above Minas Morgul in the third Lord of the Rings. Like all good mountaineers we drank equally our water when thirsty, and the view across the pinnacles at the same time. I enjoyed myself tremendously despite the pack on my back filled with water and stuff. Ever since Colombia I haven’t felt like I was truly hiking without that bloody weight on my shoulders. Knowing what I’m physically capable of always drives me to push myself when I’m in the mountains – they are havens, hospitals, and PT coaches in that way.

The stairs led all the way up to a massive pagoda 18 meters high decorated with those freaky demon-slaying Buddhist guardian creatures. A dragon stele was set outside on the beautiful stone platform. Inside was a massive Buddha mounted on a furious looking creature with the head and legs of an eagle, but the body of a man. It took up nearly the whole of the inside of the pagoda. A monk in yellow-orange robes talked to us in Chinese, though without looking directly at us as if blind. The wind was relentless and disruptive that high up, cancelling out the sun’s warmth. Taylor and I had lunch before descending a beautiful and steep staircase towards another impressive pagoda; passing exhausted manikin-phantoms as we went. Later we found out there was a cable car which led to the platform, hence their sudden appearance when before we had encountered but two people on the staircase. This pagoda was built on a concrete viewing platform on the plans of a previous temple built earlier. A naturally occurring peak existed before the concrete one, allowing visitors to stare at the largest naturally occurring image of the Buddha on earth which pilgrims had been doing for hundreds and hundreds of years. Inside the temple was a geometric and polychrome masterpiece of painting and design. Four giant guardians stood watch, crushing or impaling demons around the sides of the room. On the opposite side from the door was a window which perfectly framed the Buddha encased within the peak across from us. It was a bit of a stretch, but I definitely saw him. Can you?

A monk came into the room and began to speak with us in Chinese, explaining just what we were looking at. Beyond his hand gestures which were far more numerous than most Chinese people we had met, we understood nothing. His smile and perfect, if a little bulging, rows of teeth were worth the price of admission to the park, the city, and the country. Stepping behind one of the guardian statues, he produced two large apples, one in each hand; and walking towards us, offered them as a snack. I recognized immediately that he saw our immensely child-like gasps and grins when the apples were produced, because I felt it as soon as he made the gesture – like a child.

That was one of the best apples I’ve had in my life. I prayed to Buddha, left a donation and went with Taylor down to the cable car where we traveled back down to the mountain valleys. Further down the mountain we came into the 1000 Buddha temple (actually 1447 Buddhas,) a 16th century building chocked full of carvings – the largest collection of carving techniques from the last three Chinese dynasties in the world; the Tang, Ming, and Qing. It was all one could do to keep focus, even just enough to prevent your jaw from falling open in utter bewilderment as the true depth of the monastic menagerie sank in. All at once I felt like I was on a stage, and the 1447 figures quietly and politely awaited a masterful performance of some kind. I stayed for some time. On the way down from the mountain top Taylor and I conversed about what we had heard of in blogs as “Temple Fatigue” which is exactly what it sounds like. And I wish for all my life I could have stepped a virgin temple-goer into that magnificent cell, that amicable yet vast sea of faces and torsos and hands, all twisting this way and that in prayer, welcome, and meditation. The building itself was three tiered, and ornately made so that I noticed it immediately, even when it was surrounded by other structures of remark. Four-pointed terraces stacked opposite one another, creating eight points per level; all with eaves-a-painted with flowers and symbols of the strange disciplinary mysticism. On the inside one massive bodhisattva stood in the center of the room, while the terraced layers, though unreachable, were stacked beautifully and colorfully with figures from the faith in perfect symmetry.

As much as I longed to know each and every face no matter how impassive or impartial to my presence they were, my legs were itching for the return journey, and so I lit some incense and left in peace and calm such as I’ve rarely experienced. My trip to Qian Shan was grand, and it was nice to find an older China, even if it only reached back a couple of hundred years. It was nice to know the ragged, beaten down, city going mob of the largest nation on earth had somewhere – not just to retreat into for a day, but for a life; to live in relative quiet and harmony with the mountains, however sparse, which jumped for joy up around them like children playing among falling cherry blossoms.

It had been a mad day when Taylor and I sat down for all you can eat Chuar at a local restaurant (Skewered meat seasoned with a particular mix of spices). The craziest part had been that even at the rate at which I was spending money, split between the two of us, Taylor and I’s trip to Anshan cost only 376 yuan per person, which included, entrance to the park, six cab rides, train tickets to Anshan, and to Shenyang (China doesn’t do two-way tickets) one night in a nice hotel, dinner, and other meals. Divide that by six and you have the figure in dollars. Clearly a lot can be done in China if you have the money. Certainly one of the prettiest and wonderful lessons I’ve learned since I have been here.